If it took me a while to tell you about the remarkable Medusa exhibition at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, it’s because I needed to revisit it to better assimilate it. Indeed, my first encounter with the installation was at the opening and there was so much to see and admire that it was necessary to go back and visit it in peace. For me, Medusa is an unidentified cultural object, as the diversity of the pieces exhibited makes the event different from anything that has been presented among cultural events related to the jewellery sector. This makes it a major and unmissable exhibition.

Photograph by Evelyn Hofer (1922-2009), Anjelica Huston wearing The Jealous Husband (made by Alexander Calder around 1940). Photo: © Estate of Evelyn Hofer © 2017 Calder Foundation New-York / ADAGP, Paris 2017

Medusa. Medusa was in Greek mythology one of the three Gorgons whose gaze had the power to turn anyone who looked at it into stone. It is on this idea of the gaze that the whole exhibition is based. Because a jewel is too often an object that fascinates and that most people only see through the windows of jewellers. A high-priced object because the materials used to make it are often expensive, jewellery also raises questions about its societal positioning: religious crosses or medals for baptisms, wedding rings, engagement rings are just a few examples of this object that is by no means insignificant in our daily lives. But beyond the religious sign, it is sometimes political and can mark private events such as bereavements, as was the case until the advent of photography and the gradual disappearance of these last jewels, which I find very moving.

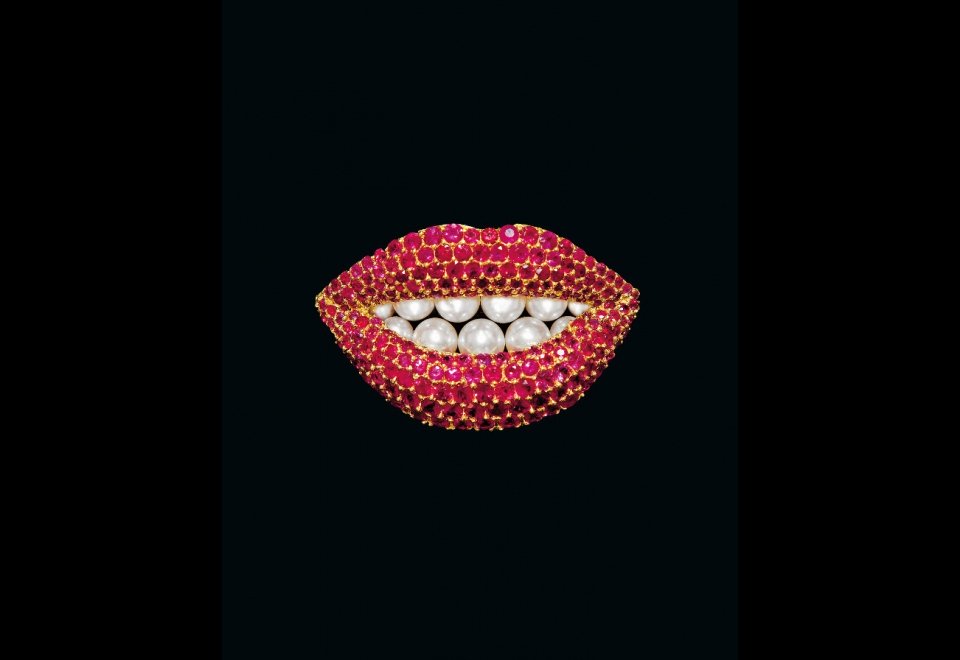

Reproduction of a Salvador Dali work by Henryk Kaston Ruby Lips, 1970-80s. Brooch, 750 gold, rubies, cultured pearls, 5.1 × 2.8 cm. Miami, private collection. Photo: © Photograph by Robin Hill

But jewellery is also a means of adornment and a means of showing off one’s wealth. It is also an inseparable element of many works where jewels (and sometimes their absence) are very present in the texts: “She had no toilet, no jewellery, nothing. And that was all she liked; she felt she was made for it. She would have liked so much to please, to be envied, to be seductive and sought after (“La parure” Guy de Maupassant, Le Gaulois, 1884), “We are expecting people, you will put on your jewellery, your bracelets. When you are rich, you have to show it” (“Grandeur et décadence de M. Joseph Prudhomme”, Henri Monnier, 1853) or again “It is not the expensive toilet and the jewels that make a woman charming. You don’t need frills and diamonds to please (“Bahamas, tome 3: Un paradis perdu”, Maurice Denuzière, 2007).

As you can see, jewellery is so deeply rooted in our culture that it is not always easy to define. It is often feminine, yet terribly masculine; it is precious but also made of glass, plastic, resin, wood, more common materials that give it its singularity; it is intended for men but also for animals; finally, it can be eaten as shown by the famous Look o Look candy necklace or the pasta necklace that we have all given to our mothers!

Meret Oppenheim (1913-1985), Bracelet, 1935, Paris, fur and metal. Private collection. Reproduced with the kind permission of the private collection © ADAGP, Paris 2017. aDAGP, Paris 2017.

So this is where the Medusa exhibition is interesting, as it confronts different worlds questioning the preciousness of objects through the prism of our own culture. What is jewellery? What is not? What is not? The curator of the event, Anne Dressen, in collaboration with Michèle Heuzé and Benjamin Lignel (scientific advisors), proposes to conceive of jewellery in a different way. I can only advise you to discover the sober and efficient staging, which reveals surprising, rare and atypical pieces, but also more traditional, touching and even story-telling pieces, such as Saint-Exupéry’s bracelet. Among the designers, you will find and discover great names in jewellery such as Cartier, Boucheron or Mellerio; but also Jean Cocteau, Dali, Pol Bury, Suzanne Syz or Galatée Pestre whose pieces inspired by lost jewellery touch me more particularly.

Serpent necklace, Cartier Paris, commissioned in 1968, platinum, white and yellow gold, 2,473 brilliant-cut and baguette-cut diamonds for a total weight of 178.21 carats, two pear-shaped emeralds (eyes), green, red and black enamel. Cartier collection. Photo: Nick Welsh, Cartier Collection © Cartier

The exhibition is on at MAM Paris until 5 November 2017. It is not to be missed as it will give you a different perspective on jewellery. At the same time, the event continues online on the exciting website run by journalist Sandrine Merlé – The French Jewelry Post – which is Medusa’s digital partner for the occasion. You will regularly discover many anecdotes about the pieces presented through dedicated articles. So there is only one thing left to do: go to the museum!

Medusa

Museum of Modern Art in Paris

Tuesday to Sunday from 10 am to 6 pm (Thursday 10 pm)

See you soon!