Watches and I have a complicated relationship. Since my twenties, I have not worn a watch. Alarm clocks often prevent me from sleeping, clocks and their damn ticking annoy me. And yet, I look at the watch industry with curiosity. I don’t know anything about it, I don’t work in that field, and when a watch catches my attention, it’s first of all for its aesthetics. Then, of course, if it has something to do with astronomy, I’m more likely to like it. If a watch tells stories, like the “poetic complications” of the house of Van Cleef & Arpels, it earns extra points. Let’s be clear, jewelry is rarely far behind in the timepieces that speak to me. But watchmaking in general remains very obscure to me. It gained a little more importance when I became more familiar with Geneva, where I go regularly. So when I started following watch consultant and historian Antoine Géraud on the gram, I really enjoyed it. A Pateck Philippe exhibition in Geneva gave us the opportunity to exchange a first mail, but we finally met in person a year ago at GemGenève. From there, time doing its work, it appeared obvious to introduce him to you and ask for his help to better understand the yang of the jewelry industry. At this point, time doesn’t really matter anymore. So just take yours and join Antoine along to discover what causes his heart to vibrate. Encounter with a lover of time.

M. Antoine Géraud. Photo fournie par M. Géraud

1- Can you introduce yourself in a few words to our readers?

I was born in the South of France, at the time of the bowl cut hairstyle and synthetic velvet pyjamas. But I always thought that I was born on the wrong side of the Pyrenees because where I feel at my best is in Spain, where I spent a very large part of my childhood.

I grew up in a family composed mainly of lawyers, surrounded by the Dalloz civil codes, which motivated me, out of a pure spirit of contradiction, to consider other areas of interest. I remember that I became interested in Fine Arts and painting very early on. This encouraged my parents to buy me an encyclopedia about art, which I spent hours and hours perusing. As a child, I loved reading too, and books have always accompanied me ever since.

Subsequently, and after an unsuccessful attempt at medical school, I returned to my first love for painting, and devoted myself to studying art history in Paris. Then, as per the friendly advice of Maître Beaussant (auctioneer), I moved to England, to attend the Christie’s school which prepares you for the art history diploma of the Royal Society of Arts in London.

That’s how it all started.

2- Before talking about what you do now, a question I ask all my guests: what job did you want to do when you were a kid? And what job are you doing now?

As a child, I wanted to be a secret agent, and when we played with my cousins we used to invent gadgets and adventures worthy of the James Bond saga. Then I went through a “plane pilot” phase because of the movie Top Gun. And since I never do things halfway, I piloted small aircrafts from the age of 15 till 18 years old, but my level in Math and my bad eyesight did not allow me to pursue this career dream (which was more, I admit it now, a whim).

Since then, I have had the pleasure of working for more than 25 years in the world of fine art auctions and in the luxury watch industry. Today, I am an independent consultant and work on commercial development projects. In addition to this, and for several years now, I have been teaching on subjects such as the history of watchmaking and its Maisons, the history of luxury, and auctions. Knowledge transfer, whether academic or purely product-oriented, is a mission that I very much enjoy.

Extract from the Instagram feed of Antoine Géraud, aka Watches and the gang. Photo: Antoine Géraud

3- Many people know you as Watches and the gang, the watchmaking equivalent of the fabulous Jewels and the gang account held by Vanessa Cron. Why this name and what is your feedback from the game of gram?

You flatter me by using the term “many”. My Watches and the gang account is very very small and confidential, especially compared to Jewels and the gang (which currently has 43K followers !). The credit for the idea of opening this account goes to Vanessa herself (Vanessa and Jean-Marc have been great and dear friends for over twenty years). One day, during a conversation, Vanessa told me she regretted there were not really any watch accounts on Instagram that talked about the world of watches in a simple way, without any geek attitude or esotericism.

This is how this project germinated, and how it finally took shape. The intention of this account is therefore to share my watchmaking crushes, or to address somewhat technical subjects, in order to play down a field which may seem complex and which is however not only the prerogative of specialists in the sector.

As for the Watches and the gang name, I asked Vanessa for permission to use it, mirroring her account name, and she of course agreed. But hey, you know what, this name was already her idea when we started talking about it together. And I am now very grateful to her for encouraging me to open an account inspired by hers, and for her trust !

When I embarked on this adventure, however, I did not realize the requirements and the work that it was going to generate : finding high definition images in order to be able to publish them, being on the lookout for information and finding anecdotes, constantly checking the veracity of the shared information, animating the social network. But ultimately all this work fulfills the historian that I am, and challenges the historian 2.0 that I have become. And the most beautiful part of all this is the encounters, the online conversations, and the links that are forged with people who are just as curious and passionate.

Workbench in a watchmaking workshop. Photo : Antoine Géraud

4- Your career path is quite impressive, what is your background and how did you end up in the Swiss watch industry?

As I told you, by academic training I am an art historian. I remind my Luxury Bachelor students of this all the time to show them that by giving yourself the means, you can become whoever you want to be in life. It takes work and passion, but you should not be afraid to redirect your career path if the urge arises : we only live once ! Creating opportunities is key, and personally speaking “sky diving without a parachute” towards new horizons has never held me back.

More seriously, I don’t think my background is impressive, but what I’m sure of is that I’ve had the opportunity and the chance to devote myself to different subjects, fields and professions that I’m passionate about. And therefore, I consider myself as a “Swiss army knife”. (Previously I would have said a “one-man band”, but since I became a French-Swiss binational a few years ago, I prefer this definition now.)

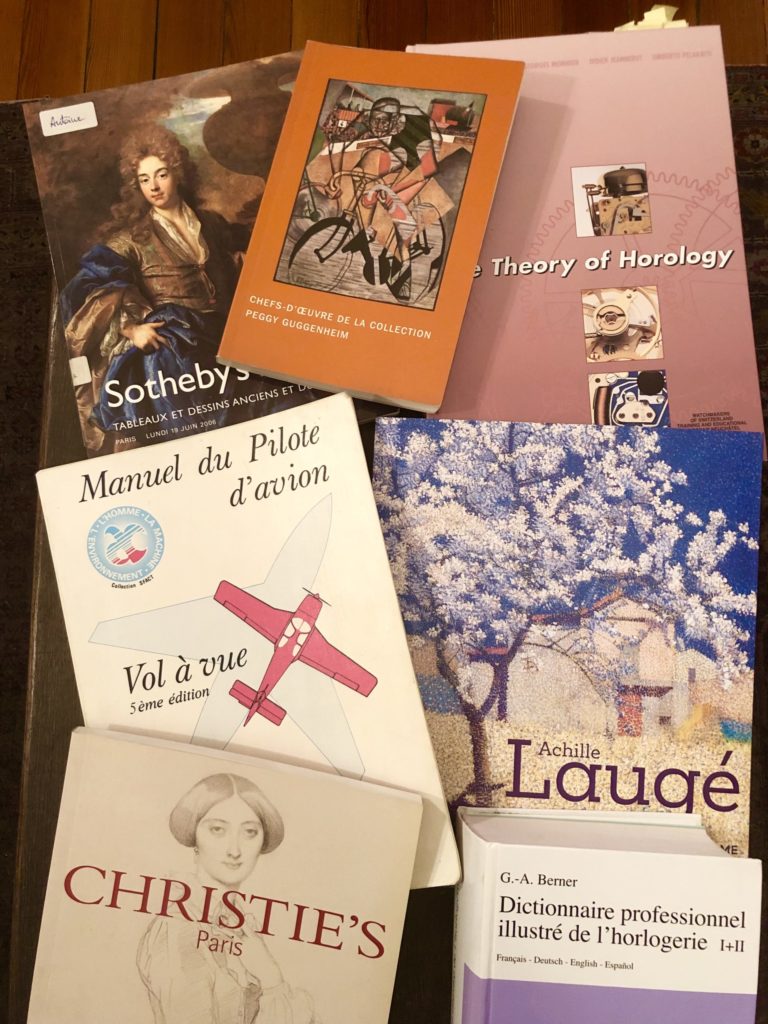

In my professional debut, and after an internship in Venice at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, I worked for many years for the main international auction houses, Christie’s and Sotheby’s, in London then in Paris, successively in departments specialized in Picture Frames, Old Master paintings and drawings, 19th century paintings and Russian art. Then another “sky dive without a parachute” lead me to the shores of Lake Geneva for a brief adventure in private aviation, which was immediately followed, having replied to a job offer on the aptly named jobwatch.ch website, by the discovery of the fine Swiss watchmaking industry, on the manufacturing side, within a historic house emphasizing the art of craftsmanship and artisans: Bovet Fleurier. Like many people, I was interested in watches, but only knew the little that a generalist weekly magazine had been able to teach me up to then (the internet did not yet offer access to as much information as it does today). This new experience of seven years (a lifetime !) as General Manager for the Asia-Pacific region for this Maison opened the doors of a new market to me, and above all that of a manufacture where I made some very beautiful encounters with designers, dial makers, craftsmen, watchmakers, and most importantly my friend Hervé Schlüchter (then conductor of this production site) who taught me what fine hand-made watchmaking is !

Some books to recap the Antoine Géraud’s career. Photo : Antoine Géraud

5- The art market, aviation, today watches, what have you preferred so far in your career?

How many Jokers do I get for the interview? Now you are already asking me a tricky one, and knowing you, I don’t think it will be the last one either…

I have enjoyed all the areas I have been involved in. And if I had to extract a common denominator from all these experiences, I would retain the human interaction and the transmission of the values of the art and luxury professions, whether it be works in museums, or watchmaking decoration and micromechanics.

Jewelery watch “Perles de Glace Rose” by Van Cleef & Arpels. Photo: Antoine Géraud

6- Watches are regularly contrasted with jewelry. Yet stones allow them to be put together. Are these two worlds really so different from each other?

If you compare a jewelry workshop with a watchmaking workshop, you are looking at two distinct, even opposite worlds. As you know so well, a jewelry workshop is a real mess. There is everything everywhere, you touch the pieces with your fingers, the material shavings are collected into a pouch affixed to the workbench, the stones are in contact with each other. There are of course similar steps in the manufacturing and the preparation of raw materials at the very beginning of the watchmaking process. But then very quickly everything is handled in the most orderly environment possible, where the slightest speck of dust could have dramatic consequences on the chronometry (i.e. time accuracy) and the proper functioning of a watch. In the factory I worked for, visitors had to put on a lab coat and blue plastic overshoes before entering the workshop, which was a ‘clean room’. There, a system of light atmospheric pressure was directing the dust in the air to be pushed down to the floor where it was vacuumed by a ventilation device through perforations in the floor tiles.

Generally, watchmakers receive the kits to be assembled on their workbench in the form of a box with compartments in each of which there is an element of the movement (wheel, screws, hairspring, etc.). The watchmakers, who wear latex protection on each of their fingers, then manipulate the components using a pair of tweezers. At each new stage of the movement assembly, they place it under a bell-shaped glass cover to avoid any interaction with the workshop environment. Looks like NASA ! In watchmaking there are two very important production poles that come together to create the assembled timepiece : the external parts (everything that is visible, such as the case, the bracelet and its buckle, the dial), and the caliber (the micromechanical movement that will animate the displays and functions of the watch). The slightest scratch, eyelash or speck of dust on the dial or the movement, and the watchmaker has to take everything apart, clean it and check everything again ! And this is not an aesthetic whim. Indeed, mechanically speaking, the slightest foreign body or friction in the movement can lead to a loss of time accuracy of the caliber which has been designed upstream using complex equations and knowledge of physics of materials (resistance, tribology : study of friction, etc. ). Nothing can disturb the mechanical perfection required in watchmaking.

When presented in this way, one would indeed think that jewelry and watchmaking would be two very different worlds. But the use of precious stones and metals, the care and meticulousness of the work, the quest for beauty, the continued presence of these two activities in the history of mankind (because yes, the history of Watchmaking also dates back to the Paleolithic period !), the creation of important factories and Maisons, the passion of craftsmen transmitted to collectors, all these parameters for me bring together jewelry and watchmaking within the same large family. And there is nothing more beautiful than jewelry-watches to prove it !

By the way, to confirm this, you saw me in the corridors of the recent GemGenève jewelry show.

The Iris Alt watch. Photo : Business Montres

7- While jewelry is now very concerned with ethics, what about watchmaking?

Like jewelry, watchmaking has also become aware of the importance of the implementation of better controlled supply chains. While the ‘conflict diamond’ scandal led to the creation of the Kimberley Process in 2000, similar initiatives sprung up shortly afterwards with regard to the mining of precious metals, such as the Fairmined label, created in 2004.

Personally, I was only confronted with the question of ethics for the first time in 2016. I was representing an independent watch brand at the Basel Fair. A lady walked into the booth and her first question was, « Sir, do you know where the gold used to make your watches comes from? » Seeing that I was unable to answer her, she explained that she was promoting ethically and ecologically mined gold as an alternative sourcing solution. Today we are still in the early stages of such an ambitious project, but a Maison like Chopard is already using ethical and sustainable gold for some of the iconic models in its collections, and also for the Palme d’Or that it produces every year for the Cannes Film Festival.

On a completely different scale, I am discovering more and more projects from watch component suppliers whose philosophy is to propose ethical or recycled materials. I was able to see this for myself at the last EPHJ (Environnement Professionnel Horlogerie-Joaillerie) trade fair dedicated to the world of high precision, which was held in Geneva last June.

I also had the chance to participate with students in a support mission for the Iris Alt watchmaking project launched by Valérie Minassian. Valérie has imagined a new feminine watch (the last prototypes have just been made) which is attentive to the environment and to people, created in 100% recycled stainless steel, set with synthetic diamonds (I know this is a vast subject of debate for lovers of gemstones), mounted on a marine leather strap made from fish skins collected from the food industry, and whose dial is entirely made of ZEP 15.10 (an alloy made from the ashes of garbage bags).

Now watchmaking houses and groups are also increasingly sensitive and vigilant with regard to ethical issues, as demonstrated by the CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) programs promoted on their various sites. I can see that the watchmaking industry is now also concerned by this subject.

8- Jewelry is currently facing a real “boom” in its economy and is cruelly lacking qualified hands (at least in France), what about watchmaking?

I do not have such a comprehensive view of all the workshops in the Swiss watch industry, but so far as I know, I have never heard of any shortage of skilled hands currently on this side of the Jura. I often meet young people who have trained as operators or watchmakers and who are looking for positions in a workshop. I therefore deduce that the skilled workforce is still there at the moment. Nevertheless, a recent report published by the ‘Convention patronale de l’industrie horlogère’ (the watch industry employers’ federation) indicates the importance of training and recruiting qualified young staff to compensate for the many artisans’ retirements to come, and to meet the new growing needs of this sector.

It is important to understand that the watchmaking industry is truly a standard bearer of the Swiss Confederation’s industries. Moreover, during the quartz crisis at the end of the 1970s, when Asian electronic watches invaded the world watch market and when the number of watchmaking employees in Switzerland dropped from 89’000 to 33’000, it was first the Swiss government and Swiss banks who intervened to bail out the industry. It was then brilliantly revived thanks to the visionary actions of Nicolas G. Hayek (with the creation of the Swatch watch and the first major watchmaking group in history) and Jean-Claude Biver (with the revival of fine traditional watchmaking).

I therefore believe that the Swiss watch industry prepares itself well to meet the demand of its booming economy.

Audemars Piguet, Royal Oak référence Ref. 15510ST.OO.1320ST.01. Photo : Audemars Piguet

9- From your point of view, what are the major challenges for the watch industry?

Mechanically speaking, watch design is a constant challenge between “little brats” (I say this with great affection). It’s the race to who will offer the flattest, largest, smallest, lightest, most expensive, simplest, most complicated, most futuristic, most innovative, best decorated watch. So mechanically, I am convinced that we will continue to discover wonders.

As far as the industry is concerned, we are increasingly witnessing a split between brands whose models are highly coveted (Rolex, Patek Philippe, Audemars Piguet, Richard Mille in particular), independent watchmakers, and the rest of the market. Indeed, social networks and the rise of crypto-currencies have created a hypertrophy of interest in some models, resulting in a demand that is faced with a limited production capacity (in watchmaking, things are done well and meticulously), or also with an economic desire to make a product rare in order to preserve its exclusive character. As a result of this demand-vs-supply imbalance, some Swiss watches have turned into speculative valuables, bought never to be worn but acquired by “flippers” for the sole purpose of being resold profitably, to the detriment of others models and other brands.

In some boutiques, a customer who has no history with the watchmaker is not entitled to make a purchase. If by chance the collector is known by the watch brand, they may be placed on a waiting list of five to twelve years, after a ‘job interview’ (nowadays we speak more and more of ‘customer recruitment’ in marketing and sales strategy). And now we even hear that a watch brand is asking customers to write a cover letter to gain access to the supreme grail of being placed on the coveted waiting list ! (I can see you judging me out of the corner of your eye : yes, I’m from the South and I tend to exaggerate everything, but the cover letter story is true !).

Recently I even read on a social network the testimony of a great watch collector visiting Geneva who was refused access to a brand boutique from its very doorstep, because there was nothing that could be shown to him for six to eight weeks. Imagine his disappointment, and what this influential collector now thinks of that brand, which did not even receive him… Admittedly, some watchmaking houses are beset with too many requests, but I believe that a critical point has been reached which is damaging the image of some watchmaking houses in the industry. Watchmaking is not snobbish and it is not only for a well-informed elite.

One of the prizes of the last GPHG the Grönefeld 1941 Grönograaf watch which won the Chronograph Watch Prize. Photo: Antoine Géraud

10- What would you say to someone who is resistant to watches to make them like and wear them? (Like me, I don’t wear them, I find them heavy, cumbersome and the models I like are expensive)

To be interested in watchmaking, you don’t have to fall into it when you are young like Obelix in the magic potion. I am a good example of this.

For me, the best way to make people love watchmaking is to share with them what happens in the workshops. Seeing the watchmakers at their workbench, talking to the craftsmen (there are more than 40 different jobs involved in producing a watch : stamping, chamfering, polishing, etc.) are the best way to fully appreciate the challenge of creating a timepiece. It is the people who work in the factories who speak the best about watchmaking, not me, not the store sales associates, not even the CEOs of these watchmaking houses.

And in watchmaking there are plenty of watch categories, as emphasized by the GPHG (Grand Prix de l’Horlogerie de Genève) which awards each year in November prizes for the best men’s watch, the best ladies’ complication watch, the best tourbillon watch, etc. With so much diversity, how could you not find a watch that would be suitable on your wrist?

So yes of course, and as you point out, we also sometimes like models that are financially too expensive and too exclusive. But if you could afford everything at the snap of a finger, there would be no more fun ! Personally, as I am lucky to live in Geneva where major watches auctions are held, I take advantage of the pre-sales exhibitions to admire and try on models that I would not have access to in a boutique. If you wish, you may join me next time.

Nevertheless, with regard to watches that are very popular, as we unfortunately see better and better well-executed copies of these iconic models, I am intransigent : you either wear a real watch on your wrist (the result of years of development and hours of work in a workshop), or you don’t. But to give in to the temptation of a copy is unacceptable for me !

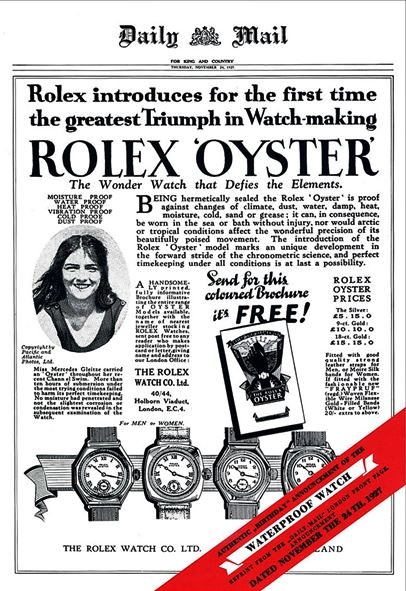

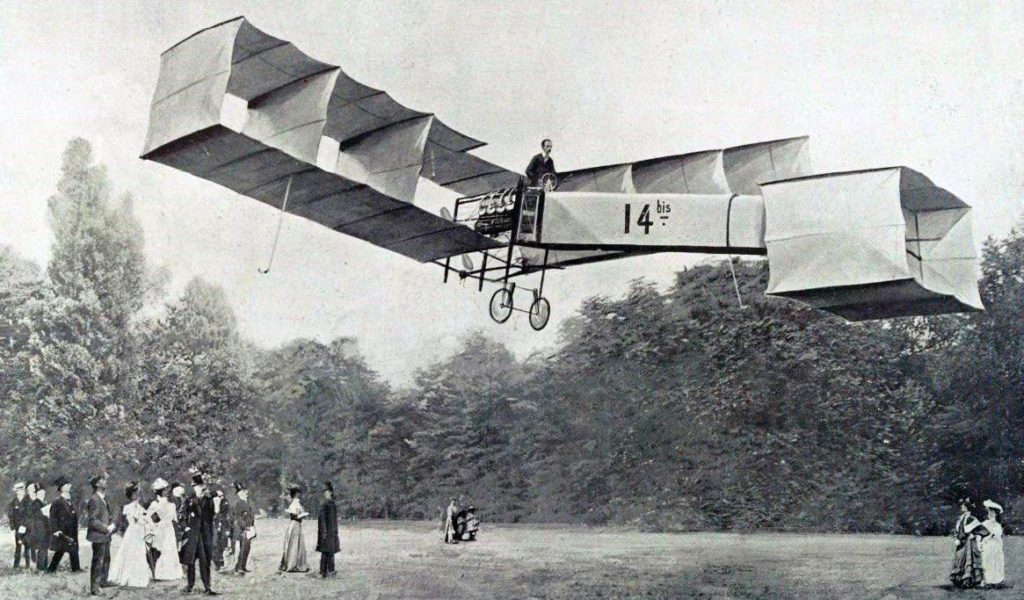

(1) The Breguet 160 watch made for Marie-Antoinette. Photo: Swatch Group. (2) The Daily Mail article illustrating Mercedes Gleitze when she swam across the English Channel in 1927 ; (3 & 4) Santos-Dumont in his plane and with the watch created by Cartier (photo 4 from Saffronart Blog). (5) The watch made for George III by Breguet. Photo: gov.uk. (6) Portrait of George III by Alan Ramsay 1762.

11- Do you know any watch stories? Just like jewelry and stones, where you can find all the possible anecdotes, from the most flashy to the most improbable, do watches have their stories?

Of course, watches have their stories too ! But how much time do you have ? I’m talkative, you know…

I could tell you about watch number 160 created by Abraham-Louis Breguet himself for Queen Marie-Antoinette. Neither of them saw it finished, one because of age, the other one because of the Revolution. The watch was stolen from a museum in 1983, whereupon the house of Breguet decided to produce a replica (number 1160), and at the same time the original watch reappeared.

I could also tell you about the watch that Hans Wilsdorf, founder of Rolex, placed around the neck of Mercedes Gleitze when she swam across the English Channel in 1927, in order to take advantage of this sporting achievement to prove the water resistance of his Oyster case.

I could also tell you about the extravagant Brazilian dandy Alberto Santos-Dumont, an aviation enthusiast, for whom his friend Louis Cartier designed the house’s first men’s wristwatch, the famous Santos, to allow him to read the time on his wrist so he would not have to read it on a pocket watch, which caused him to take his hands off the controls of his aircraft whilst flying.

But I’m going to tell you about a watch that recently stirred the opinion of British watch lovers. During the Napoleonic campaigns, Europe was divided by an embargo which isolated the British Isles. King George III of England, a great lover of fine watchmaking, commissioned Abraham-Louis Breguet in Paris to make a pocket watch with a tourbillon regulator, his brand new mechanical creation, a watchmaking complication that compensates for and reduces the effects of the earth’s gravity on the movement. Despite being forbidden to trade with the perfidious Albion, Breguet created the watch in 1808 under the manufacture number 1297, as listed in the historical ledgers of the house. But instead of bearing the Breguet signature and the hallmark of Tavernier (his watch case manufacturer), the watch was signed Recordon, who was none other than Breguet’s London correspondent through whom the royal order had by then arrived in France, and it had been stamped with the hallmark of Comtesse, the case maker of the latter, established in Soho. It is assumed that King George was of course aware of the provenance of this exceptional piece, which has a tiny hidden Breguet engraving in the movement, on the tourbillon carriage. In 2020 this historic watch was sold at auction in London by Sotheby’s to a foreign collector, for the amount of £1,575,000, and now, to be able to keep it in the Kingdom collections, a group of enthusiasts is trying to raise funds to reimburse the buyer of this exceptional timepiece, blocked for the moment on British territory because it is awaiting its export certificate.

12- What would be for you the book to read or the documentary to watch to start learning about watchmaking?

We have very fine watchmaking museums in Switzerland (among others the Patek Philippe Museum in Geneva, the Atelier Audemars Piguet Museum in Le Brassus, the International Watchmaking Museum in La Chaux-de-Fonds, the Watchmaking Museum in Le Locle, or the Omega Museum in Biel). But it is perhaps best to begin a first initiation by reading a book like “The theory of Horology” by Reymondin, Monnier, Jeanneret and Pelaratti (translated into many languages) to understand the watch caliber and its functioning. All the watchmakers I know have this book in their library.

Then, even if it is a little more technically advanced, “The art of Breguet” by watchmaker George Daniels is another watchmaking bible that one should have browsed through.

Finally, you can find very beautiful monographic books on such-and-such watchmaking houses: “Patek Philippe: the authorized biography” by Nicholas Foulkes, “Royal Oak – Audemars Piguet” by Martin Wehrli, “Cartier – The Tank watch” by Franco Cologni, numerous works on Rolex, to name a few.

Personally, I prefer books to documentaries, but many quality bloggers also offer their platform on the internet and the gram (@horology_ancienne, @thewatchestv, @the_vintage_lounge, @repeticiondeminutos, @sjxwatches for instance). And there we sometimes witness quarrels over points of view between purists and…purists, depending on the belief of each of them.

(1) During the Dubaï Watch Week en 2017. (2) At the train station in Taichung, Taiwan, after an event in 2014. Photo : Antoine Géraud

13- Do you have a story to tell us about your career? A story that would have marked you these last years?

I had the chance to represent Swiss watchmaking in more than twenty countries, mainly in Asia, and each of these many trips is a wonderful memory.

There were of course episodes with unforeseen events, such as the time when the miniaturist dial painter who accompanied me to Taiwan was detained on arrival by the airport’s air and border authorities, because his passport had expired three weeks previously. After more than six hours of negotiation and calls to embassies and chambers of commerce, he had to immediately fly back to Europe on his own, entrusting me with his binoculars, demonstration watch dials, and his equipment (pigments, brushes, etc.) when he was the reason for our on-site event the next day. That very day I had to take his place to host this event, and as “Murphy’s Law” had decided that the stars were not aligned for me, the organizers had placed a camera on the workbench to broadcast the work counter at a large scale on a giant screen placed just behind my chair. Throughout the cocktail I tried in vain, under the curious eyes of the guests, to put on a brave face and paint whiskers on a tiger, which I had to immediately erase with turpentine given my poor talent. The endless remarks of my drawing teacher at school resonated at the time: “Not beautiful at all Géraud !”. Today, this miniature painter and I are still friends, and we still laugh about it !

Another moment that marked me was a meeting with a very important multi-brand retailer in Tokyo, in his small eponymous shop in the Shinjuku district. I was presenting a minute repeater watch, one of my favorite horological complications, which consists in a chime system that allows the time to be struck on demand (hours, quarters and minutes after the last quarter) using circular gongs placed around the movement. And to really “listen” to the watch I was offering, the shop owner asked his sales team to bring us three minute repeaters from three different brands to compare them with the one I was showing. We listened to them and re-listened to them one after the other, balancing them flat on a sheet of paper held by hand to amplify the sound of the chimes. This was followed by a discussion on the construction of repetitions and how to technically improve their sound. It was a great watchmaking lesson punctuated by a great sale.

Beyond these anecdotes, I had the chance to meet great collectors, and great watchmakers too, like the much-appreciated Philippe Dufour, whose kindness and modesty are noteworthy.

Excerpt from an Antoine Géraud’s course on the Tank watch by Cartier. Photo: Antoine Géraud

14- For several years you have been teaching around watchmaking. What do you like about this aspect of your professional life?

Teaching and sharing a subject that fascinates me is a real pleasure. There must be of course an element of selfishness at the beginning, when I do my research and work on the organization of my ideas. Not least because I am constantly discovering new information that builds my thinking and my ideas. But it is above all the transmission that motivates me, as when I gave product training courses while visiting my markets around the world.

I was also lucky enough to welcome many industry professionals for various talks I organized at school, and to become a student myself again whilst listening to their knowledge and experience. I particularly remember the encounter with Anita Porchet who came to talk to us about the art of traditional manufactured grand-feu enamel. Madame Porchet had brought samples of colored glass, palettes, some equipment and dials she was working on at the time. We were all fascinated by her work, her talent and the works of art we were able to admire that day. I have very good memories of this beautiful moment, and that is why I love teaching.

15- How do you see the industry and its future?

The watch industry is a very varied world, made up of the houses of the major groups, independent watchmakers, component suppliers, communication professionals, collectors and bloggers. So, of course, we look at financial interests, stakes, strategies, quarrels, small circles and communities. But all these facets are part of the microcosm that is the watchmaking world, and I look at it with high regard.

As for its future, I am not worrying. The notion of time, its measurement and its passage, have fascinated humankind since the dawn of time. And even if today we easily know the time thanks to our mobile phone, the dashboard of our car or the front of the oven in our kitchen, mechanical watchmaking will live on because its poetry allows us to admire the time that escapes us and flees. Tick tock, tick tock !

Patek Philippe perpetual calendar and chronograph ref.1518, signed Cartier (1945) sold for CHF 2,214,000 at Christie’s Geneva on Nov 22. Photo : Antoine Géraud.

16- Watch auctions are well known with big names coming back regularly. But should we expect any surprises in terms of quotations in the years to come?

As you so rightly say, big names come up regularly in auction catalogs (Patek Philippe and Rolex represent on average 75% of the lots offered). This is mainly due to the difficulty of being able to buy the collections of these houses directly in a store, which leads to a craze for their models on the second-hand market. As with the art market, only exceptional pieces or iconic references fetch prices above the catalogue estimates, while the rest of the watches on offer sell for more reasonable prices.

However, I am not sufficiently specialized in this market to say what the future trends are, but we can certainly expect new surprises, both in terms of results and future interest in new references.

(1) Furlan Marri “Mare Blu” watch. Photo: Furlan Marri. (2) Louis Cartier “Tank” watch. Photo: source unknown. (3) Haldimann “H1 – Flying Central” watch. Photo: Haldimann. (4) Krayon “Anywhere Métiers d’Art” watch. Photo: Krayon

17- What is your favorite house and why?

I was afraid you would ask me this question, and this is where I would have liked to play my second Joker !

In watchmaking, we like some watches for their design, others for the good craftsmanship of their caliber, for their mechanical complications, or sometimes just for the watchmaker who orchestrates behind the scenes. So I am going to give you an evasive answer by not replying to your question directly, but by listing several watches, as a catch-all inventory.

A designer watch : If you are looking for a watch with a vintage style, look at the collections created by Furlan Marri. The watches are elegant, timeless and affordable.

A shaped watch : The house of Cartier excels in shaped watches, and of all those offered by this historic house, my favorite model is the Tank watch, the classic version, with the Louis Cartier case. (And speaking of Cartier, I cannot help but mention the wondrous Crash watch from 1967 which proves highly coveted today whenever a model is offered at auction.)

A tourbillon watch : Without hesitation, I quote here the “H1 – Flying Central” by Haldimann. It is a wristwatch whose case measures 39mm in diameter, with a tourbillon in the center of the dial. The proportions of this model are perfect.

A complicated watch : I love the “Anywhere Métiers d’Art” timepiece presented by Krayon. This timepiece allows, thanks to its ephemeris function, to indicate every day of the year the time of sunrise and sunset according to any location anywhere in the world, and this in an entirely mechanical way!

A dream watch : It would be a 38mm diameter watch in white gold with a blue guilloché dial, a World Time module displaying the 24 time zones, inspired by the one created in the 1930s by Louis Cottier, coupled with a minute repeater…

M. Hervé Schluchter. Photo : copyright @madeinbienne

18- Are there any promising young houses emerging on the market? Which ones should be followed closely?

So you just asked me a question in the singular and I answered it in the plural, well here your question is in the plural and I will answer it in the singular (in the spirit of contradiction).

For me, the most promising watchmaker is without hesitation my friend Hervé Schlüchter, who created his own watchmaking workshop in Biel. And I’m not talking about him here just because we’re friends. Hervé is objectively a very great and very promising watch designer.

Throughout his already very long career Hervé has created sublime timepieces, including an exceptional astronomical watch: the Asterium. Today, Hervé’s universe poetically combines the extremely large, drawing inspiration from celestial events, with the notion of time-passing on the intimate scale of the wearer of the watch. I had the chance to discover many extraordinary and innovative, highly advanced projects, that he has imagined, but for reasons of confidentiality, I cannot share them with you here.

And all of this is designed from components that he shapes and manufactures, thanks to old artisanal machine tools, acquired with passion in order to preserve traditional fine watchmaking, as in the time of the founders of the great historic watchmaking houses that we know today. If I were to compare Hervé to a jewelry designer according to my modest knowledge of the world of jewelry, his creative project would be similar to that of Emmanuel Tarpin, for example, to give you a better idea.

19- Finally, what advice would you give to a young person who wants to work in this sector? What should they choose? What path should they choose?

The jobs in the watchmaking field and industry are numerous. I will therefore quickly go over the commercial and marketing activities that can be addressed in programs devoted to Luxury Management, such as the one offered for example by the school CREA in Geneva.

But I know you’re passionate about craftsmanship, and I’m guessing what’s really on your mind with this question. As I have already told you, to really simplify things, there are two main fields of work in watchmaking: the external parts of the watch, and the micromechanical construction. I think there is already a choice to make between these two sectors.

If it is pure watchmaking at the workbench that attracts you, watchmaking schools in Switzerland and France are a compulsory step for training and proving yourself.

If, on the other hand, you are more interested in the activities of the decoration (enameling, guillochage, engraving, gem-setting, etc.), then there are other training courses available in schools, particularly in the Bernese Jura, which can then be completed by apprenticeships in a workshop or at a brand.

Anyhow, a person who embarks on a career in watchmaking will be constantly learning. Confirmed and renowned watchmakers continue to train in techniques which complement their know-how, or develop new techniques to push the boundaries of their profession a little further.

Luxury and watchmaking are showing a growing renewed interest in the markets following the pandemic we have been through, and I can only encourage vocations in this very beautiful industry.

See you soon !