Regularly in the auctions, one sees passing jewels presenting Essex crystal. Most of the time, these pieces of jewellery are adorable, a bit kitschy but very nice. These are pieces of rock crystal (sometimes glass or crystal), cut into cabochons, engraved and painted from the back to take advantage of the magnifying glass effect and give relief to the painting, which is therefore located at the back of the piece. The most beautiful examples are engraved in intaglio and then lined with mother-of-pearl, but sometimes a simple mother-of-pearl or ivory plate is painted and enhanced with this quartz “magnifying glass”. The effect, of course, is completely different. Most of the jewellery on the market with this technique is English, as the country was a great lover of this fashion during the Victorian era (1837-1901). I have often read that these pieces were so named because they were made in Essex, or that it was the miniaturist painter William Essex who started this trend, as he was the enamel painter to the Queen and thus to her husband, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, from 1839. Although the origin of the technique is not obvious, William Essex had few to do with the technique that bears his name. So let’s try to put things in order.

Platinum, diamond and pearl brooch, circa 1910. Available on 1stDibs. Photo: 1stDibs

Most sources on the origin of this technique cite a supposedly Belgian artist named Ernest Marius Pradier who, around 1860, is said to have initiated the technique. Ernest Marius Pradier did exist. He was born in France, in Paris, in the 3rd arrondissement. Only he was born on 3 October 1881. We are more interested in his father: Ernest William Pradier, an engraver, born in England in 1855, who married Clara Jane Leggatt in London in 1879. How the couple ended up in Paris in 1881, living at 1 Boulevard du Temple, is a mystery. In any case, the Pradier family is known to have made pieces with this painted crystal from the 1870s onwards. If the passage through Paris is confirmed by the French registry office, the Pradiers went to England and the father set up a renowned workshop in London around 1896/1897, then the son followed in Bedforshire in the town of Dunstable from 1932. It was with his father that Ernest Marius learned his trade. The workshop will distribute its animal productions in Europe and even in the United States. There was also a long and profitable partnership with the London firm of Longman & Strongitharm. Tiffany & Co. and even Cartier are known to use this type of painted crystal, possibly with Pradier’s productions.

Gold and Essex crystal brooch, Tiffany & Co. circa 1930. Sold at Skinner in September 2013. Photo: Skinner

Finding the origin of painted crystal requires cross-referencing several sources to try to get a clearer picture, but the first English productions can be dated to around 1860. The possible origin of these glass or rock crystal cabochons seems to be with the Thomas Cooke company (not Thomas Cook, the travel company) which manufactured scientific apparatus including glass elements and more particularly lenses. In later years, the name Thomas Bean became regularly associated with this technique. Although a glass manufacturer born in 1855 in York was named after him, there is little documentation of him. The little information available describes him as having been an apprentice to Cooke.

Then it was time to engrave and paint these cabochons. It was at this point that engravers and intaglio specialists were called in, followed by miniature painters.

Essex gold and crystal bracelet with a maritime theme, circa 1940. Photo: 1stDibs

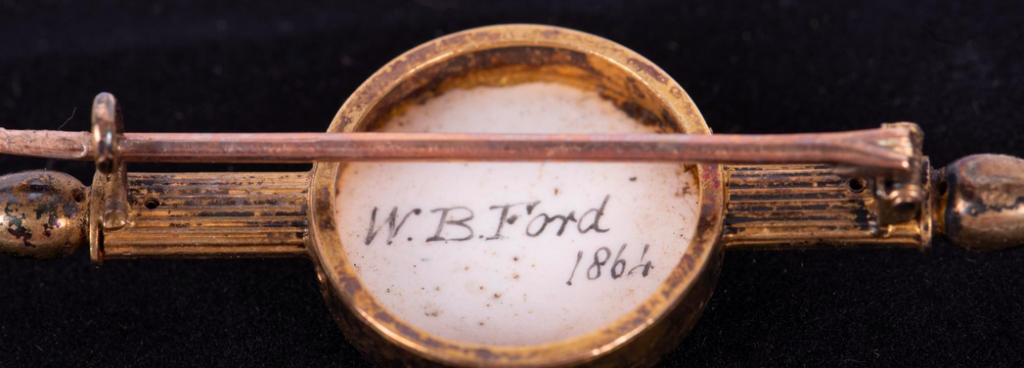

William Essex gave his name to the technique, but we will see that it was one of his pupils who popularised it. He was the official miniaturist of Princess Augusta of Cambridge, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He was born in 1784 and died in 1869, just a few years after the first examples of “Essex Crystal” appeared on the market. In reality, it was William Bishop Ford who popularised the technique. Born in 1832 and dying in 1922, he was a pupil of Essex and assisted him in his workshop at 3 Osnaburgh, Regent’s Park in the 1850s and 1860s. His work in Essex crystal is well known at auction and the earliest, to my knowledge, dates from around 1864. There are also pieces bearing his signature, a rare enough example to be noted.

Gilt metal and Essex crystal brooch, signed by William Bishop Ford in 1864. Sold for $450 in St. Louis, Missouri by Link Auction Galleries in October 2022. Photo: Link Auction Galleries

Essex crystal had its heyday in the second half of the 19th century. However, beautiful pieces with floral, animal and sporting subjects could still be found until the 1920s and 1930s. From the 20th century onwards, bad copies in plastic and glass became more common. The factories on the other side of the Rhine produced large quantities of moulded glass, which could be multi-layered and painted. The result is nothing like the fine work of the often anonymous engravers and painters who excelled in England in the late 19th century.

So, to buy this type of jewel, take a magnifying glass and look carefully at the relief of the painting. Properly made pieces have a real 3D effect. Pay attention to the quality of the paint and the choice of colours and shades. And above all, buy a subject that you like. This advice cannot be repeated too often when buying jewellery.

Gold and crystal cufflinks from Essex. Sold at Lyon & Turnbull in 2015 for £875 premium inc. Photo: Lyon & Turnbull

See you soon!