In recent years, celestial jewellery has made quite a comeback in designer showcases and high jewellery collections. In the last few years alone, the“Under the Stars” collection by Van Cleef & Arpels, unveiled in January 2021, the“Heaven ” collection by Chaumet, several pieces in the “Stopover in Venice” collection and of course the latest“1932” collection for Chanel, which wonderfully celebrates the astral theme, come to mind. Amongst the independent jewellery designers, we can think of the “Astronomica” collection by Jenny Dee and the “Sirius” or “Mysterious Star” collections by Elie Top. There is no doubt that the stars, the moon, the stars, the sun or even distant galaxies never cease to feed the imagination of jewellers who enjoy transcribing into metal and gems this mysterious starry sky that is not easily tamed. Starting from these current references, it was time for the star lover that I am to propose a brief history of celestial jewellery.

1- Instant T, a comet named 1P/Halley

in 1705, at the height of the scientific revolution, Edmond Halley – an English astronomer and engineer – published a work that would become a milestone in the history of astronomy: A Synopsis of the Astronomy of Comets. He had been studying the sky since the 1670s and became fascinated by the stars. After studying at Queen’s College, Oxford, he sailed and catalogued the stars of the southern hemisphere. He was also responsible for the discovery of the constellation Centaurus in 1677 when he took up the work of Ptolemy and Johann Bayer. In his 1705 book, he questioned the passage of a comet in 1456, 1531, 1607 and 1682 and hypothesised that it was the same comet that reappeared in the sky every 76 years. He then predicted its return in 1758, basing his theory on the elliptical orbit and the estimated time to complete one revolution around the sun. Halley died in 1742 and his predictions were not verified. It was not until 1757 that Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande took up Halley’s calculations and adjusted the date of the comet’s passage. Based on the possible deviations of the comet due to the presence of planets, he announced a delay due to Jupiter and Saturn and refined the comet’s passage for the beginning of 1759. When the comet appeared in December 1758 with a perihelion (The perihelion is the point in the trajectory of a celestial object in a heliocentric orbit that is closest to the Sun) on 13 March 1759, it was an absolute triumph. It definitively established Newtonian mechanics in France. This passage allowed Halley’s calculations to be certified and the comet was named after him.

(1) Bust representing Edmond Halley at the Royal Observatory Museum, Greenwich; (2) Halley’s Comet in 1986; (3) Commemorative plaque at Westminster Abbey. Photos: Wikipedia

2- The “Ring in the Firmament

As the passion for the stars continued unabated, some very special rings appeared between 1770 and 1780. Made of gold and silver (platinum was not yet known), topped with a royal blue enamel plate, these rings featured a multitude of small stars or small round or star-shaped settings. It was undoubtedly Marie Antoinette who popularised this type of jewellery following her coronation as Queen of France in May 1774. She was then just 18 years old and her husband was barely older than her when they both ascended the French throne. These jewels can be seen as much as an anchoring of the astral chart as a way for the men to turn to a more powerful “force”, the sky. Indeed, the queen began to wear this type of jewellery while her pregnancy was still pending (the king’s sexual difficulties were well known, as he suffered from a malformation of the prepuce, making sexual intercourse painful; as a result, he was more interested in woodwork than in trifles), and it was not until four years later that the queen welcomed her first child: Marie-Thérèse Charlotte of France, also known as Madame Royale.

(1) Ring au firmament in gold, lapis lazuli and diamonds – photo: bijouxoccasion.com ; (2) Firmament ring in gold, silver, enamel and diamonds preserved at the Walter Albert Arts Museum in Baltimore ; (3) Firmament ring in gold, silver, enamel and diamonds preserved at the Walter Albert Arts Museum in Baltimore ; (4) Painting of Marie-Antoinette by Wertmüller in 1785, in the Nationalmuseum, Sweden; (5) Detail of the painting showing two Childbirth Rings worn by Marie-Antoinette; (6) Gold, silver, diamond firmament ring or childbirth ring – photo : 1stdibs.com

Some of these rings are set with a central stone in the middle of the starry sky, like a star that shines brighter than the others. This is known as a childbirth ring. It is also worth noting that some of these pieces were mounted on glass or lapis lazuli and not on enamel.

3- 1835, the return of Halley’s comet

In 1909, the writer Mark Twain wrote “I came into the world with Halley’s Comet in 1835. It will return next year, and I expect to go with it. The Almighty said, ‘Behold these two inexplicable monsters; they came together, they must go together. The man died in 1910 and with this sentence testifies to the mystery with which men surround Halley’s comet. If in 1758 the world was not really ready for the passage of the star, in 1835 everyone was waiting for it. And jewellers were not left out. From this date onwards, small brooches and even some rings appeared to honour the passage of the damsel in the sky. Most often, these pieces are made of silver and gold with a multitude of coloured stones, including glass. While most are precious, not all are. Perhaps you have even seen some without knowing that they were Halley-related? They are found quite regularly at auctions, so keep an eye out for them!

A set of brooches dedicated to Halley’s comet. Garnets, citrines, pink topaz, amethysts, pearls, rubies, sapphires, diamonds and glass paste. Sold at Christie’s in November 2020 for £5200. Photos: Christie’s

4- Jewellery dedicated to the North Star (Victorian era and after)

More than the North Star, it is the stars that find their way into jewellery in the mid-19th century. There were several reasons for this, but above all important archaeological discoveries that led to the rediscovery of forgotten civilisations and a renewed interest in lost cultures, most of which used the sky as a tool for determination. The spiritualist movement also developed rapidly during the same century. In Anglo-Saxon countries, the Witchcraft Acts regulated the practice of witchcraft until the middle of the 20th century. This sounds incredible, but it is true. Behind this interest in history, spirits, death or at least the cult of what has disappeared, we must above all place the context of an era turned upside down by the industrial revolution. This interest in what is no longer is a form of anchoring, because what is no longer can’t change and that is reassuring. Jewellers therefore seized on this phenomenon. The portrait of Sissi with star jewels in her hair (Franz Xaver Winterhalter, 1865) comes to mind. And so we see jewels with stars in general or jewels with Polaris or Stella Maris, this polar star, symbol of hope and affection, which gives the North and orientates those who are lost…

(1) Large necklace transformable into a silver and gold tiara, diamonds, circa 1870. Sold at Christie’s in 2017 for £317,000; (2) Silver and gold, diamond and opal brooch, circa 1880. Photo: Lace jewels; (3) large gold, diamond and turquoise brooch, circa 1880, sold at Fellow’s; (4) gold, diamond and enamel brooch, circa 1870. Photo: FWC Jewelers

5- Crescent moons (Victorian and later)

Like star jewellery, moon-shaped jewellery was also very fashionable in the second half of the 19th century. The reasons for this are more or less the same as those given in the previous paragraph on star jewellery. But in this case, in addition to the classic association between the moon and the feminine symbol, the moon has a more precise origin in the rediscovery of the Greco-Roman civilisation. Perhaps the expression “lunar triad” is not foreign to you, it symbolises the three goddesses around the moon: Selene, Hecate and Artemis in Greek (Luna, Hecate and Diana) symbolise respectively the full moon, the new or black moon and the crescent moon. They were of course highly honoured in their time and even today Wicca movements continue to celebrate Hecate, the goddess who enables communication between the earthly and the invisible. In Mesopotamia, there was Ishtar, goddess of war, love and life. The Sumerians worshipped Inanna who had similar attributions. You will find many texts on the subject if you are interested. I assure you that it is absolutely fascinating. The jewels decorated with one or more moons are therefore very symbolic jewels, turned towards the feminine and they are sometimes completed with this famous good star. The motif can be found on all types of jewellery and is often embellished with diamonds, turquoise, various gemstones but especially opals.

(1) Platinum, diamond and green stone (emeralds?) tiara, attributed to Chaumet, circa 1910. Sold for €58,000 at Tajan in July 2022; (2) Gold moon brooch and demantoid garnets. Russian work, late 19th-early 20th century. Photo: romanovrussia.com; (3) Gold, fine pearls and engraved glass ring (possible transformed brooch), late 19th century. Photo: Erica Weiner; (4) Gold and silver brooch, diamond, circa 1870. Photo: Adin.

6- The conquest of space (from the 1950s)

Although moons, stars and comets were still regularly used by jewellers in the early 20th century, it was not until the end of the 1950s that there was renewed interest in jewellery inspired by the sky. But these were to take a more spatial turn for a very simple reason: it was time for men to conquer space! And it starts with the successful launch of Sputnik 1, on 7 October 1957 at exactly 19:28. In doing so, the Russians inaugurated what would be called the Space Age! Sputnik” jewels were born. Of all types and sizes, they are set with numerous stones but can also be all gold. Costume jewellery was not left out and the designers of the time embraced this trend! That said, these jewels also take on the look of other satellites that will make history in space such as Luna 1 or San Marco 1 and even Asterix.

(1) Cartier sapphire brooch, late 1950. Photo: Christie’s; (2) H. Stern earrings in gold and various gemstones, 1950s-1960s. Photo: 1stdibs; (3) Gold Cartier brooch, 1960s. Photo: Miller; (4) H. Stern gold and peridot ring, 1950s-1960s. Photo: 1stdibs; (5) Cartier gold, diamond, ruby and sapphire earrings, 1960s. Photo: Christie’s; (6) Gold, diamond, ruby and sapphire brooch, unsigned, late 1950s.

In 1958, the Americans entered the race with the successful launch of Explorer 1 and NASA was officially created on 29 July of that year. The next ten years would see a battle for control of space with mainly two countries competing in this field: the USA and Russia. Jewellery inspired by the appearance of the moon soon appeared, because since 1959, and the images provided by Luna 3, we began to know more about this satellite that is essential to life on earth. One of the first pieces of jewellery directly inspired by the appearance of the moon’s surface dates from 1961. It was made by Roy C. King Ltd.

Moon Crater necklace in gold, enamel and diamonds. Sold in 2017 at Chritie’s. Designed by Roger King, made by Roy C. King Ltd for Garrard & Co. The “Moon Crater” bracelet and earrings were exhibited in the 1961 “International Exhibition of Modern Jewellery 1890-1961” at Goldsmiths Hall and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The set won 1st prize in the De Beers Modern British Jewellery Competition at Goldsmiths Hall in the same year. (1) and (2) Photos: Christie’s; (3) Photo: The Goldsmith’s Company

(1) This platinum and diamond Rocket Ship brooch, late 1950s, was sold at Lang Antiques. There is no hallmark to link it to a house. Photo: langantiques.com. (2) A similar brooch by Cartier also exists, late 1950s. Photo: Christie’s

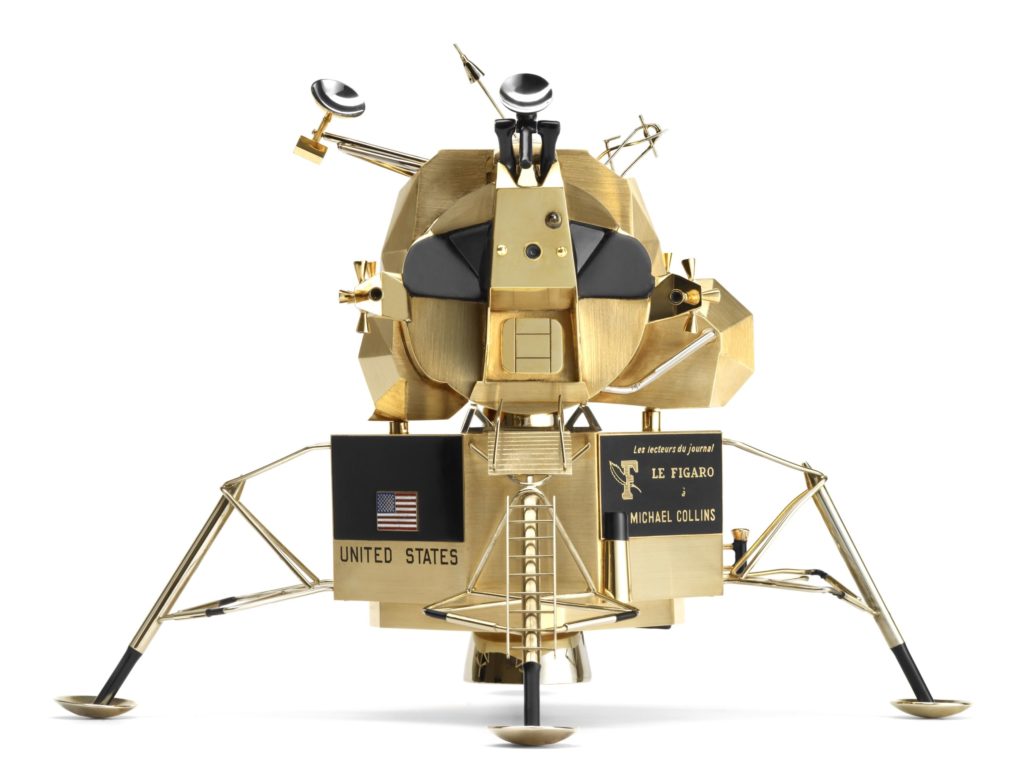

The climax of this Space Age found one of its most important conclusions with the Apollo 11 mission when, on 29 July 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the moon. On that day, millions of people watched this event live, which was to mark the history of space worldwide. From that date onwards, and throughout most of the 1970s, jewellery inspired by the moon and this event flourished among designers. But one of the most unusual objects made was this replica of the lunar module that came out of the workshops of the House of Cartier.

Three copies of the lunar module were made by Cartier at the request of Le Figaro and thanks to financial donations from readers. Neil Armstrong donated his to the Armstrong Air and Space Museum in his hometown of Wapakoneta but it was stolen in 2017. Cartier acquired the one that belonged to Michael Collins in 2003 for $55,000. Photo: RR Auction

The 1970s were rich in pieces evoking the Apollo 11 mission, and one occasionally comes across pieces belonging to Neil Armstrong, for example, at specialist dealers or auctions. Designers have also been inspired by this moon, which has become less mysterious with successive exploration missions, even though no man has set foot on the satellite’s surface since 1969. One example is the work of jeweller Tapio Wirkkala, whose work is widely recognised and exhibited in the world’s greatest museums. Another example is the hammered gold bracelets of Jackie Kennedy Onassis, which are reminiscent of the surface of the moon, but for which Van Cleef & Arpels has always spoken of an Etruscan influence.

(1) Gold, silver and enamel brooch, 1969, by Pierre & Jacques Leysen. Only ten brooches were made. Photo: 1stdibs; (2) & (3) Gold and ruby brooch by Van Cleef & Arpels, former Neil Armstrong collection, 1969. In photo 3, his wife is wearing this jewel to meet Elizabeth II. Photos: M. S. Rau; (4) Gold and ruby moon pendant by Van Cleef & Arpels. Photo: Vogue; (5) & (6) Gold earrings made by Ilias Lalaounis for Jackie Kennedy Onassis in the early 1970s. In photo 6, Jackie Kennedy Onassis is wearing them. Photos: Sotheby’s

7- Astrological jewellery (1970 and after)

It is impossible to talk about celestial jewellery without mentioning the jewellery representing the signs of the Zodiac. Although we know of a few examples before the Second World War, the trend really took hold at the end of the 1960s and during the 1970s. Although astrology has been practised for thousands of years, and was even the mainstay of civilisations that have now disappeared, the appeal and large-scale development of horoscopes appeared after the Great Depression of the 1930s. History has remembered the publication in 1930 of Princess Margaret’s natal chart in the Sunday Express, creating a craze and popularity that has never been denied. What newspaper today does not have a horoscope section? The figures speak for themselves: in France, it is estimated that almost 40% of the population read their horoscope more or less regularly and that more than 90% of French people know their astrological sign. Jewellery could not miss this trend.

(1) Zodiac bracelet in yellow gold, white gold and rubies, circa 1970, Cartier; (2) Aquarius brooch in gold, platinum, diamonds and emeralds, mid-20th century, David Webb; (3) Virgo pendant in yellow gold, platinum and diamonds, 1970s, David Webb; (4) Libra pendant in yellow gold, mid-20th century, Tiffany & Co. Photos: 1stdibs

8- What about today?

To be honest, we haven’t seen the last of stars, moons, suns and comets in jewellery designs. The sky is an endless source of inspiration for designers and jewellery houses have not waited to propose entire collections dedicated to the celestial theme as I mentioned in the introduction to this article. One example is the “Les galaxies de Cartier” collection, which featured the planets, a motif that was rarely used in jewellery until recent years. And watchmaking is not to be outdone. As early as 1925, the House of Cartier designed the “Sky” clock.

(1) “Lumières de la terre” bracelet in gold, diamonds, sapphires and fire opals by Cartier. Photo: Cartier; (2) “Galileo” ring by Van Cleef & Arpels, gold, diamonds, sapphires, rubies and rhyolite. Photo: Van Cleef & Arpels; (3) “Tremblig stars” clock in gold, inclusion quartz, rock crystal, diamonds and pyrite-inclusion quartzite. Photo: Cartier; (4) Astronomia watch by Jacob & Co. Photo: Jacob & Co. ; (5) Lady Arpels Planetarium watch. photo: Van Cleef & Arpels

See you soon!