in 2018, fighting against the presence of synthetic diamonds seems to me to be a challenge, as it is completely improbable. And yet, it is clear that this subject is very divisive in the jewellery industry. Let us be very clear, synthetic diamonds , or “laboratory-created diamonds“ if we refer to the English term, now officially represent 2% of sales in a market estimated at over 70 billion dollars. Recognised as existing since a statement by General Electrics on 15 February 1955 declaring the successful creation of “diamonds designed by the hand of man, (…) the result of nearly 125 years of effort to reproduce the hardest and most glamorous substance produced by nature”, these stones are now a reality. If it is necessary to fight on a certain number of points, it is firstly on a problem of naming which raises today a more than important legal concern and, secondly, on marketing arguments whose reality risks, in the long term, to see disappointing many customers.

1- The “cultured” Diamond appellation has no place

On this specific point of this contentious case, it is necessary to refer to several texts, but above all to understand what lawyers call the “pyramid of norms”, which makes it possible to classify and position legal texts in order of importance and application, whether they are French, European or international. Because yes, the law that applies on French territory is not only the result of discussions by French legislators.

Let us return to our synthetic diamond. In France, the law governing names in the field of gems is called Decree n°2002-65 of 14 January 2002 relating to the trade in gemstones and pearls. It is a regulatory standard. Article 4 is the one that directly concerns us in this case. It says precisely that the term “synthetic“ is that which one must use “for the stones which are crystallized or recrystallized products whose manufacture caused completely or partially by the man was obtained by various processes, whatever they are, and whose physical properties, chemical and crystalline structure correspond essentially to those of the natural stones which they copy“. Whether synthetic diamond is HPHP (high pressure high temperature) or CVD (chemical vapor deposition), it falls squarely within the scope of this part of Article 4.

Further on in the text, but still in Article 4, it is specified that “Theuse of the terms: “bred”, “cultivated”, “cultured”, “real”, “precious”, “fine”, “genuine”, “natural” is prohibited to designate the products listed in this Article“. Also, the current more and more widespread designation “cultivated diamond” is absolutely ILLEGAL on the French territory. As article 9 of the present decree also specifies, ‘It is forbidden to import, hold for sale, offer for sale, sell or distribute free of charge the materials and products mentioned in article 1 under a name other than that provided for in articles 2 to 8 of the present decree.This name shall be indicated on the labels accompanying the product and on any commercial or advertising document referring to it

Legally, it is interesting to go up the pyramid of standards to find out if this text does not oppose a superior text. The only superior (because international) text in existence is the international standard ISO 18323:2015 entitled “Jewellery — Consumer confidence in the diamond industry”. Published in July 2015, it will be re-evaluated and possibly modified in 2020. Unlike the 2002 decree, this is not a regulatory standard but a voluntary standard. AFNOR clearly explains that “to respond to specific situations of general interest, the administration may also decide to refer to a voluntary standard to guarantee the achievement of a certain level of protection for people or installations.The voluntary standard cited in the regulation then becomes, in this very specific case, mandatory In our demonstration, the ISO standard does not provide any further argument and is not cited in the current regulation. It explains that the acceptable terms are “synthetic diamond”, “diamond manufactured in the laboratory” or “diamond created in the laboratory”. But in France, only the terms “synthetic diamond” or possibly “synthetic diamond” are valid. This is fine with me, even if I find the term “laboratory-made diamond” easier to understand for neophytes. The point that bothers me is the confusion in common language between synthetic and artificial. I would like to remind you that a synthetic product has an equivalent in nature (synthetic because it is a synthesis of a natural formula) whereas an artificial product is a product created from scratch. Also the denomination “artificial diamond” does not have place for these stones since the chemical formula is the same as that of the natural stones.

2- Are the names “laboratory diamond”, “laboratory-created diamond” or “laboratory-made diamond” illegal?

Under the current law, there is no provision clearly stating that these designations are prohibited. But, when you read the law, they are not valid either. If these names are listed as valid by the ISO 18323:2015 standard, the fact that this standard is voluntary and not explicitly included in the decree n°2002-65 makes it – for the moment – inapplicable on the territory. That said, it may one day be applied in France. If you have any questions about the ISO standard, I suggest this article from 2015 where I talk about it at length.

3- Is synthetic diamond ethical?

In part, yes. Indeed, as long as these stones are manufactured in laboratories and factories that respect environmental and social standards, we can consider that these stones are clearly less polluting and therefore less “impacting” on humans than diamonds extracted in mining areas that are today, for example, Africa, Canada or even Russia. Let’s face it, mining, despite its considerable efforts, is far from perfect. And although most of the world’s major mines have ISO standards guaranteeing good environmental management, the damage to the environment, ecosystems and indigenous populations is disproportionately heavy. At the same time, there is the problem of reclamation of mining sites after operations. For example, the Kimberley Mine “The Hole”, whose extraction hole has never been rehabilitated, comes to mind. In the same perspective, the Russian mine of Mirny is quite frightening in the ecologically strained context of the 21st century.

The “Big Hole”. Photo: South Africa discovered

The Mirny Mine in Siberia. The Mirny Mine in Siberia. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

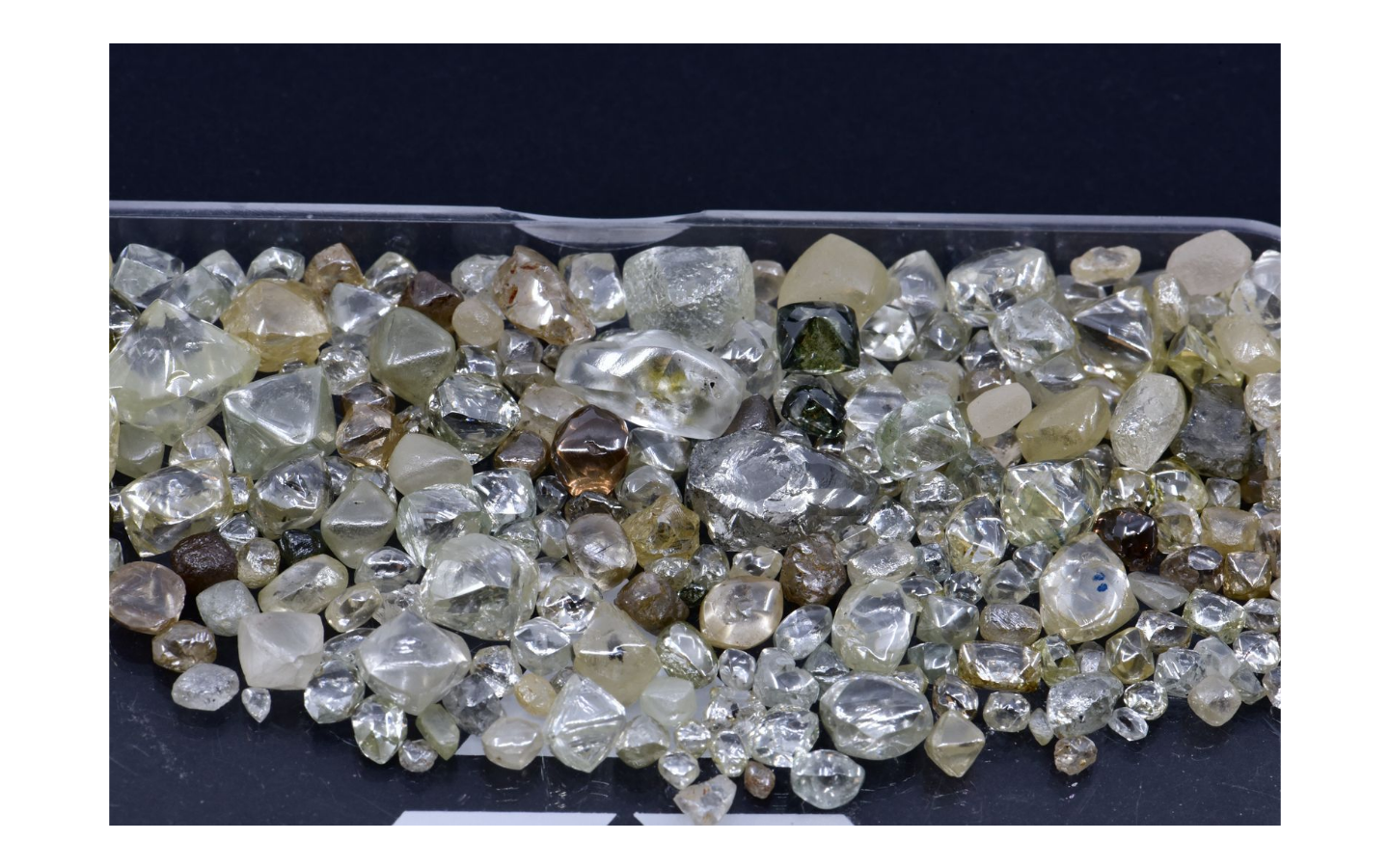

To say that diamond mining is problematic is a fact. But to say that synthetic diamonds are ethical is not a complete reality either. Today synthetic diamonds are produced mainly in Russia, China and also in the USA, which also happens to be one of the most polluting countries in the world. If I can hear and respect the ecological commitment of a company such as Diamond Foundry (based in San Francisco) whose production is entirely ensured thanks to solar energy and with a closed circuit for water, to incite to the acquisition of Chinese synthetic diamonds whose manufacturing conditions are more than opaque is much more complicated. I would therefore moderate the ethical argument unless I am completely sure, with figures to back it up, that the impact of the manufacture of these stones is less for everyone involved in the value chain. I don’t doubt that it is, but I would like to know exactly how much. Perhaps the brand will one day open its facilities to the press? In any case, I also have to admit that these stones are absolutely amazing. And I speak as a gemologist. Clearly indistinguishable to the eye, these synthetic diamonds do not have to pale in comparison with natural diamonds. Here, nothing to do in terms of quality with emeralds or synthetic corundum that a good gemologist can detect quite easily. We have clearly taken a technological step forward!

Communication campaign from the American-based company Diamond Foundry. Ad film from the American-based company Diamond Foundry. ©DiamondFoundry

*****

In conclusion, we can say that synthetic diamonds are well represented on the market. Whether it is sold as such or whether it can infiltrate batches of natural stones, it is necessary for the consumer to have complete information and if not, not to hesitate to ask for it. In France, the Laboratoire Français de Gemmologie is competent in the analysis of gemstones and will be able to certify your stone or stones. It should also be noted that the LFG has decided not to grade synthetic diamonds. But that several world laboratories decided, of which the GIA, to apply the 4Cs almost completely in their entirety. Among the significant modifications, the scale of the colours is simplified and does not include the letters reserved for natural diamonds. This desire of the American laboratory is met with criticism. For my part, I find the desire to provide clear information for the customer interesting. Even if it must be borne in mind that synthetic diamonds have no financial value on the auction market for the moment. However, if this information makes it possible to give an order of value for a natural stone, a synthetic stone will not be valued at the time of an expertise. Diamond Foundry offers its customers an automatic credit on the purchase of a synthetic stone which represents 100% of the value of the stone. An initiative that can reassure.

Today, each side is sharpening its marketing and commercial weapons. Natural diamonds have their customers and no doubt synthetic diamonds will find theirs. They have already found them and will continue to have them. With prices 30-40% lower (and certainly more over time) than natural ones, they are clearly accessible to customers who could not afford the equivalent produced by nature. And that’s good news. There has to be something for everyone. De Beers has just positioned itself in this market in a rather clever way. First of all, remember that “cultured diamond” is not a legal designation and that a certificate must accompany your stone. This last recommendation is valid for natural diamonds. Whatever the stone you buy, acquire it in accordance with your values and your budget, but don’t be afraid to ask the seller for clear and sourced information. Finally, bear in mind that a piece of jewellery is not an investment but can become one. The resale of a synthetic diamond will not yield any profit. We have no hindsight on these stones and we cannot predict how the market will integrate and manage them in 20, 30 or even 100 years. For example, other synthetic stones have little value in the new market and no value in the old or second hand markets. To avoid disappointment over time, it is therefore absolutely necessary to know what you are buying.

See you soon!