The world of jewellery is full of exciting and passionate people. Most of the people I meet on my way are passionate about their subject or their speciality. Listening to them speak is to travel with them and to be nourished by what they are. So I’ve been crossing paths with Olivier Bachet for a while now and every time I see him, I learn something. I had already interviewed him about the publication of his beautiful book written with Alain Cartier about the objects of the eponymous house. We had also organised a presentation at Sotheby’s Paris and the idea of a real interview on his career made its way into my mind. I therefore propose that you discover this long and fascinating interview with Olivier that we have put together over the last few days. He tells us about his career, his love of Cartier objects, his editorial adventure, art and everything that nourishes him in his professional practice. Meet him!

Mr. Olivier Bachet. Photo: Olivier Bachet

1- Can you introduce yourself in a few lines?

Originally, I am an antique dealer specialising in the purchase and sale of antique jewellery and 20th century display objects. I am a member of the Syndicat National des Antiquaires (SNA) and a founding member of the IAJA (International Antique Jewelers Association).

In general, people who do this job fall into two categories: either they take over from their father, who often took over from his father, in short, it’s a family affair, or they are self-made and have become dealers by chance and providence. I’m a bit of a mixture of both. I was co-opted in a way by my friend Gilles Zalulyan, director of Palais Royal, who gave me my foot in the door and with whom I’ve been working for over 20 years now. It was easy, we had been neighbours and inseparable since we were 8 or 10 years old and we did the 400 coups together. But on the other hand, I learned a lot on my own, especially when I specialised in the work of the House of Cartier.

2- What has been your career path up to now?

I had a very “classical” education. I have always been passionate about history and I have never asked myself any questions. From a very young age, I knew that I would be a historian and I can tell you that I had no little ambition. Like Hugo who wanted to “be Chateaubriand or nothing”, I wanted to be “Fernand Braudel or nothing”. Well, today, 30 years later, I am nothing (laughs), at least in terms of history, because after the first year of my thesis, I was caught up by weariness and by the prospect of working with Gilles, who came to look for me and offered me to work with him. That’s how I got there.

Pair of platinum and diamond clips, Cartier London circa 1935. Photo: Palais Royal Collection

3- You have now become one of Cartier’s greatest experts. How and why Cartier? What do you like about the company ?

I became a Cartier specialist first and foremost out of taste. I like what this house has done, in any case, since its installation on rue de la Paix. Even if many houses have done magnificent things, and I’m not just talking about Van Cleef & Arpels or Boucheron, which most people know, I’m thinking of names that are ignored by the general public and which are nevertheless great names in jewellery, such as Janesich, Lacloche or Marchak. Of all of them, Cartier remains the one I prefer, and make no mistake, Cartier’s work is immediately recognisable to those with a trained eye – and you know why? Because since the beginning of the 20th century, Cartier has been the designer and this aspect is practically unique in the world of jewellery. I mean in these proportions. As early as 1910, there were a dozen designers working full time on Rue de la Paix.

Moreover, Cartier has the enormous advantage of having produced a lot and of having had in its catalogue the whole range of precious objects: jewellery, watches, display objects. – And it is one of the few – and what a diversity in style. There is everything, from the Belle Epoque to Art Deco, in short it is a creativity and diversity that no other house is able to offer. And as a history buff, I appreciate the fact that the people at Cartier were aware, before anyone else, of the need to preserve and enhance the heritage and archives, and to present a collection of emblematic pieces, so that it was easy to learn thanks to the fabulous exhibitions and the wonderful catalogues put together or published by Cartier. Nobody else has done this. Everyone is doing it now but Cartier did it long before anyone else.

4- How do you work when you have to carry out an expertise? Where do you get the information? What is your certification process for an object?

It is important to clarify to the readers before answering your question that little by little, taken by this passion for Cartier, I wanted to discover what was hidden behind this prestigious name, who were the makers, the designers, what the numbers and letters stamped on the pieces meant, etc. So much so that, little by little – and this is the reason why I am so proud of my work – I was able to find out what was behind this prestigious name. So, little by little – because if you want to understand everything, you have to study everything – with time and a lot of work I learned a lot and I converted to the expertise that has become my main activity today.

To carry out an expertise, there is first of all an indispensable prerequisite: to have the part in “the hand”. Then you have to know how to look carefully, not to leave anything out, not to forget a punch that would give you indications or a letter that accompanies a number for example. Depending on this, everything can change, the date but also the city: Paris or London for example..

And then the information you look for in your head, it’s our main database, and when you’ve seen hundreds of Cartier pieces you start to know what a gallery looks like, how the security of the clips or pins are made, how the stock numbers are struck, in short, experience counts a lot. For example, you know that if you have an Art Deco piece of jewellery in your hand, and it has the Cartier Paris signature on it, but it is badly made, then you know for sure that it is not authentic. There is no such thing as a poorly made Cartier Paris jewel made in 1925! Finally, there is the literature. In his book on Cartier, which is a magnificent book by the way and a must read, Hans Nadelhoffer made a mistake by giving makers’ hallmarks that are misrepresented and false. No, “false” is a misnomer, they are true in the sense that they are those of jewellers named “Cartier” and working in Paris, in other words they have the same patronymic, but in no case is there any question of the Cartier that interests us. However, these hallmarks continue to be published and reproduced, including by forgers who either fraudulently inscribe – that is to say, hallmark – jewellery or objects with the hallmarks of Cartier’s namesakes, or who engrave, just as fraudulently, objects or jewellery legitimately inscribed with these same namesakes’ hallmarks, with an apocryphal signature “Cartier Paris London New York”. Yet this misinterpretation could stop circulating if one read my book! (laughs)

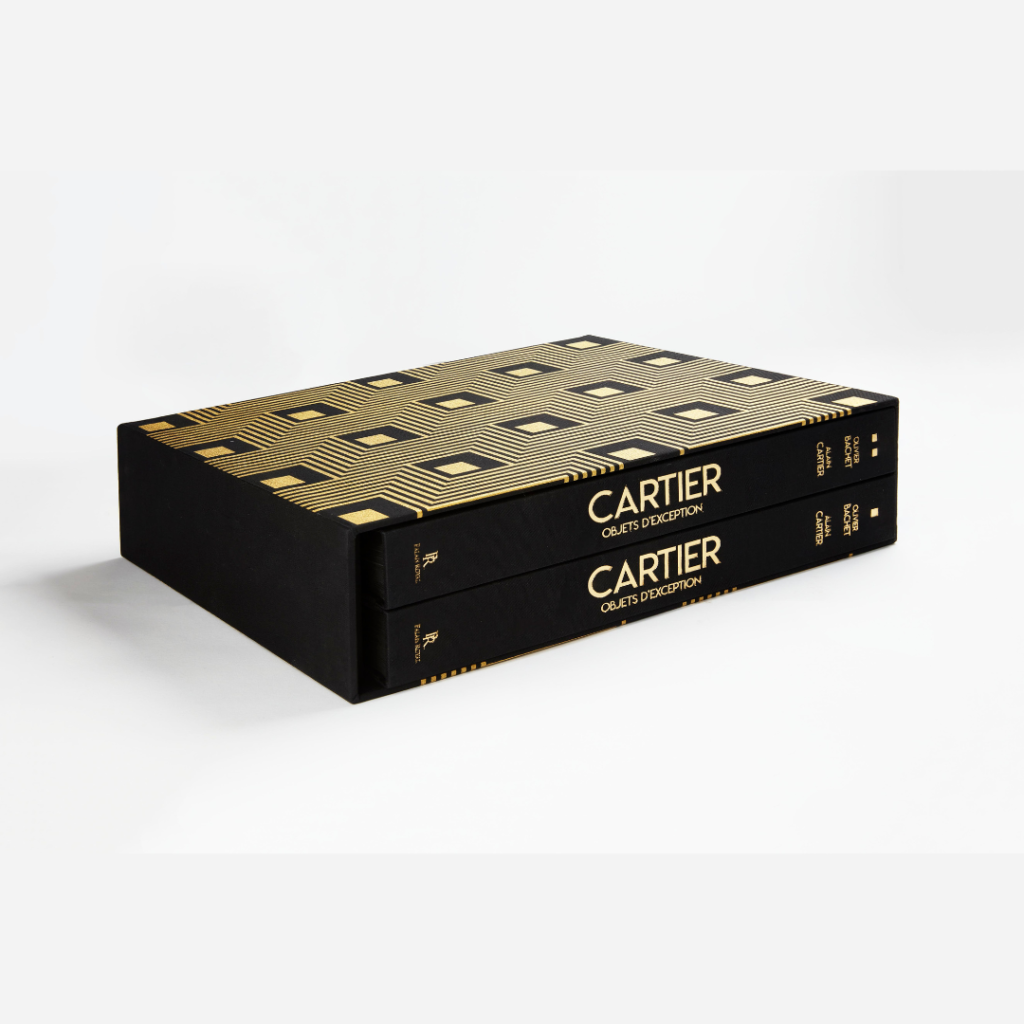

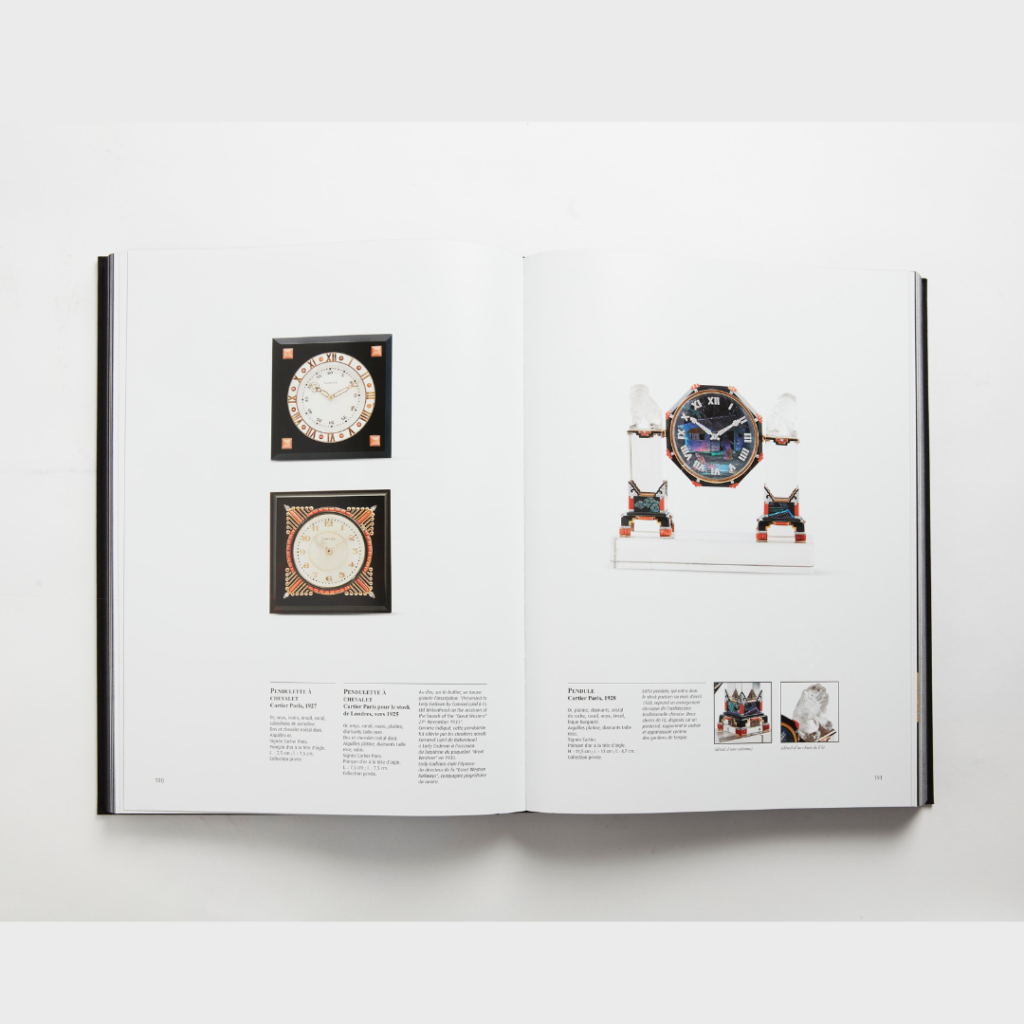

The book “Cartier, objets d’exception”. Photos: Olivier Bachet

5- You co-authored the reference book on the Cartier object with Alain Cartier. How did this project come about and why did you embark on this publishing adventure ?

In fact, it was my passion that pushed me to write this book and my desire to share it. First of all, my passion for precious objects, I think I have always preferred objects to jewellery, so this was a good match for my interests. Moreover, nothing or almost nothing had been written about objects, so it was a question of filling a gap. My job as a dealer led me to see thousands of Cartier pieces, to meet collectors, to attend public auctions or simply other dealers who had bought a beautiful piece and I said to myself: it is not possible to keep this for myself. You have to show people the treasures that Cartier made and also explain. Now, for anyone who wants to write about Cartier, there is a collection that cannot be ignored, it is the Cartier Collection, the most beautiful in the world and which no one can match. However, this has a drawback, the collection is not exhaustive, so that with each new publication on Cartier, the same pieces are always used and illustrated. However, given the immensity and variety of the production, I thought it was a shame that the other pieces were not published. In addition, Cartier, for its collection, only looks for very remarkable pieces, yet there are hundreds of objects that are not particularly remarkable but which also reflect the history of this house and it was necessary to show and describe them.

But you spoke of an adventure, and that’s right, it was an adventure. I had never written a book and knew nothing about it, so I thought big, two volumes of 1000 pages. I had to learn, surround myself with competent people, find a printer, etc. And then I wanted to make this book about objects, an object itself. I did not skimp on materials. For example, as I was not satisfied with the packaging proposed by my printer, thanks to a friend who gave me their contact details, I called on the company that makes the cardboard packaging for certain Chanel products. There, I was sure that the quality would be there. And as I wanted to be sure of the gold colour of the packaging, I had the motif printed in 24-carat gold on the cardboard. But beware whoever takes on a job like this, let them make the adage “The best is the enemy of the good” their own. If I hadn’t made it my own at some point, I think I would still be tweaking some of the details in the book.

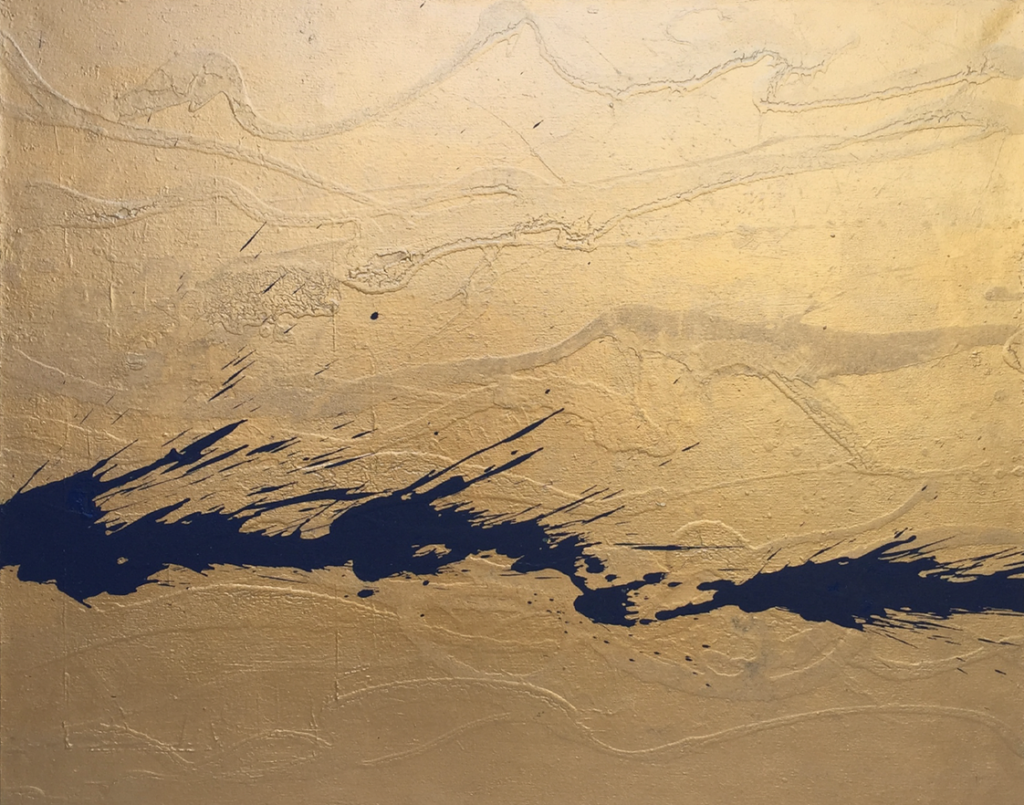

6- I discovered you as a painter during the first containment of 2020. With a japanese work that I personally find superb. What does this practice bring you in your daily life?

You are very kind and tolerant towards me. Painting brings me pleasure, pleasure and more pleasure. But you have understood well, my painting has certainly an extreme oriental side. The influence is probably to be found in the calligraphy of certain Zen masters. I sold my last painting to a Japanese woman for her gallery in Tokyo. What counts above all is the movement and as long as I am not satisfied, I start again. Sometimes I go crazy, but I am uncompromising. And in this case, the adage “the best is the enemy of the good” does not count. However, I didn’t take up painting because I was confined, I’ve been painting for a long time. What started out as a simple personal pleasure has taken a different turn. Today, I receive orders that I don’t have time to fulfil.

Two paintings by Olivier Bachet. Photo: Olivier Bachet

7- How do you continue to be moved by an object? How do you keep your eye alert without becoming jaded after so many years of practice?

I am not jaded at all and I don’t think I ever will be. I can tell you that it is the opposite. I love to see new pieces, beautiful objects or new jewels, for a simple reason, we always discover new things that fill gaps and confirm or deny beliefs. Because seeing new things allows you to put together the pieces of a puzzle, so to speak. For example, I had two brief descriptions of boxes in my archives that I could hardly imagine. Then recently, I received a request for an expertise on two Cartier cigarette cases, made in Russia by Yahr in 1904. When I saw these two objects, I could relate them to the two descriptions I had in my possession. This is exciting, especially when we are talking about pieces that have become extremely rare.

As another example, last month I received a photo from an auction house of what looked like an Egyptian-style bracelet by Cartier Paris and was asked if I thought the piece might be authentic. On seeing the photo I was skeptical, to put it mildly. I of course asked to see the piece, and well, despite appearances, it was 100% genuine, but modified as it was probably born as a dog collar rather than a bracelet. The stock number was simply an order number and so, as often happens, it was out of the ordinary. I would like to take this opportunity to say that in my opinion one of the qualities of a good expert is not to have too many certainties, to have doubts, never to be sure of anything, because there are unheard of things in the world of jewellery.

Gold, jade, enamel, coral, lapis and diamond libation cup, Cartier Paris, circa 1930. Photo: Palais Royal Collection

8- You have just launched a beautiful platform dedicated to Cartier: Cartier Collector (www.cartiercollector.com). Why this desire to share? What does it bring you?

Thank you for telling me about it, because this site is very important to me. I have devoted a lot of time and energy to it. “Cartier Collector” is a free and informative website. Please note that I am in no way taking the place of the press and marketing department of the great House, I don’t have the means to do so and this site only concerns antique pieces. When I set up this site, the idea was as follows: to exchange and share with enthusiasts or simply people who are interested in Cartier, by enabling them to find as much information as possible in a quality format and with a beautiful presentation concerning all areas: watches, jewellery and precious objects. It is a question of exhibitions, books, important pieces for sale, in-depth articles but also to give advice and opinions, in short to make a reference site concerning Cartier, its history, its production, a little like a site dedicated to old Bugatti for collectors of this brand. You will tell me that this kind of site already exists and I will answer you: yes and no. In fact, the interest of this site is to find things that cannot be found elsewhere, including useful information for professionals, concerning the punches, the numbering of the parts and others. The idea is not to talk about the Duchess of Windsor’s jewels or Cartier’s panthers again, which are not uninteresting but are outdated subjects. To do this, I have surrounded myself with contributors, including you, in order to bring a variety of perspectives on the world of Cartier. As for the desire to share, perhaps it is a reminder of what I wanted to be: an academic destined to teach.

9- What is your view of the art market? How has it evolved? And how do you see it in the years to come?

It is difficult for me to talk about the art market in general. Of course, I have some ideas but if I limit myself to the antique jewellery market in particular, I am very optimistic. First of all, the market is affected by inflation, which shows that people have a renewed interest in antique jewellery. This can be explained by several factors. In these uncertain times, the fact that these pieces are made of precious metals gives them a refuge value, moreover, there is a general awareness of quality with the certainty in people’s minds that the old is a guarantee of quality, which is not necessarily true by the way, even if it is obvious for Cartier. Moreover, the world is evolving, and buying old or second hand is no longer incongruous for young people. Today, this is done in considerable proportions, including in ready-to-wear. My own children, who are in their twenties, regularly buy second-hand clothes, whereas at the same age it would not even have occurred to me. And then there is also the Chinese market, which is very dynamic. My friends tell me that for their parents, it was unthinkable to wear old jewellery with the idea that it belonged to dead people. This idea has completely disappeared for the younger generations.

10- A place related to your profession that you should have visited at least once in your life?

All the big museums that have beautiful collections of jewellery in the first place: the Musée des Arts Déco in Paris or the Victoria & Albert Museum in London, but that is obvious. However, I can tell you about a visit related to my job that made an impression on me. When I was writing my book on Cartier’s objects, many of which are made of hard stones, I had the chance to visit the old cutting factory of what was Cartier’s hard stone manufacturer and supplier, “Berquin-Varangoz”, which later became “Fourrier”. Situated in the Brie region, this small factory is almost as it was in the early 20th century with its water mill providing power for the machines, its old tools, its courtyard, its millstones, some of which date back to the 17th century, and most impressively, piles of hard stones amongst the weeds behind the factory. In my mind and before my visit, I imagined the hard stones stored in a shed, neatly arranged on shelves by type of stone etc. But not at all, because of the quantity, weight and so on, the stones were laid in piles on the ground. As would be the case for a masonry company, where sand, bricks and tiles are stored outside. All overgrown with weeds, so you walk around and see here and there, a pile of porphyry, a pile of agates, there rock crystal, here rose quartz etc. I have only one regret, to know that all this will disappear because the last lapidary who works there is alone and without apprentice. But that’s the way it is, the production of hard stone objects no longer exists or almost, it’s the direction of history and we can’t go against it.

Brooch in platinum, diamonds, sapphires, rubies and enamel, Cartier Paris, circa 1925, customer order. Photo: Palais Royal Collection

11- What is the best advice you could give to young people who would like to do the same job as you?

I’m only going to break down open doors (laughs). First of all, be passionate. It is so much easier to do something when you are driven by passion. Secondly, consider that the appetite comes with eating and it is not because this passion is not anchored in you from the start that it will not come with time. I am speaking from experience. And then finally work, work and work some more. Looking at the pieces, taking them in hand, touching them, asking questions to the people you work with: experts, auction houses etc.

I think it is also important to be a physiognomist, to know how to recognise styles and periods. From this point of view, history has helped me. Finally, having a good general knowledge and a chronological basis that allows you to order things in your mind.

See you soon!