For a few months now, I’ve been tempted by the idea of bringing in contributors to legemmologue.com. You could, for example, read Marine Chabin ‘s excellent article on jewellery know-how. Claire Fillet with the podcast “Rubis sur Canapé” joined the adventure. Emmanuel Thoreux – now a trader in American gems with his company White River Gems – has twice taken you to the USA. Today Sébastien Bahri, Asia Manager for Nomad’s, invites you to discover the Erongo region in Namibia.

Landscape of the Erongo region. Photo: Sébastien Bahri

Landscape of the Erongo region. Photo: Sébastien Bahri

Sunset on the Spitzkoppe. Photo: Sébastien Bahri

*****

By Sébastien Bahri (FGA)

1- Introduction

A little more than ten years ago, one day in September 2008, I was walking the aisles of the Bangkok trade fair with a group of students from my gemology school when our attention was drawn to a rather unusual stand and especially to its display cases. That day, I met my future (and current) employers from Nomad’s in the flesh and I also discovered Erongo’s tourmalines for the first time. It was a double revelation. Today, ten years later, I can see those tourmalines in my mind. Electric blue, mint green, bright yellow, blue-green, they still haunt my memories. Some love at first sight is unforgettable!

So when the opportunity arose to go to Namibia to visit their mine of origin, it was a “yes” without hesitation.

Neon blue tourmaline from the Usakos mine in Namibia, from the pocket discovered in 2005. These stones, very similar in colour to Paraiba tourmalines, are virtually impossible to find on the market today. Photo: Jinjuta Lohacharoenvanich

2- A little history and geology

From the huge diamond concessions in the southern Sperrgebiet to the Marienfluss mandarin garnet deposit in the north, from the amethysts of the Brandberg to the dioptase of Tsumeb and the aquamarines, jeremijevites, tourmalines and demantoid garnets of Erongo, Namibia is an extraordinary country. One could write entire books on Namibian gems, so this short article will only focus on tourmalines from the Erongo region. I admit that I am not impartial, I have been under the spell of these stones for a long time..

Erongo is a gigantic caldera of about 30 kilometres in diameter, the remains of an ancient volcano that was active about 135 million years ago. After a violent eruptive phase, the volcano collapsed completely, forming the caldera visible today. This eruption was followed by a second phase of granite intrusion into the caldera and the area around it. Numerous pegmatites were created, containing numerous crystals, including tourmaline, in internal cavities or ‘pockets’.

The presence of tourmalines in the Erongo pegmatites has been known for about a century. Hans Cloos, a famous German geologist, made geological maps of the area and carried out on-site studies before the First World War. The mining of the pegmatites is still largely done in an artisanal way, with pickaxes, chisels and crowbars, which is absolutely exhausting physical work.

Some miners make their own black powder to blow up the blocks of rock. When they have the financial means to do so, they use pneumatic jackhammers to break up the pegmatite. The lack of fuel for the compressor is sometimes a problem.

Landscape of the Erongo region. Part of the Erongo volcano caldera is visible in the left background. Photo: Sébastien Bahri

3- A visit to a mine

Most of the mining activity in the region is concentrated in an area around the towns of Omaruru, Usakos and Karibib. While there are several dozen small operations and independent miners chasing the elusive pocket of tourmalines, only two larger mines are still in operation, Usakos near the town of the same name and Katjanga, about 40 km south-east of the town of Omaruru.

The quantities of gem-quality tourmaline mined from Erongo have never been able to compete with the plethora of production in Brazil or other African countries, but they are no match for other sources in terms of quality. The blue, indigo and neon blue tourmalines, as well as the blue-green “lagoon” tourmalines produced in the region are undoubtedly among the most beautiful in the world.

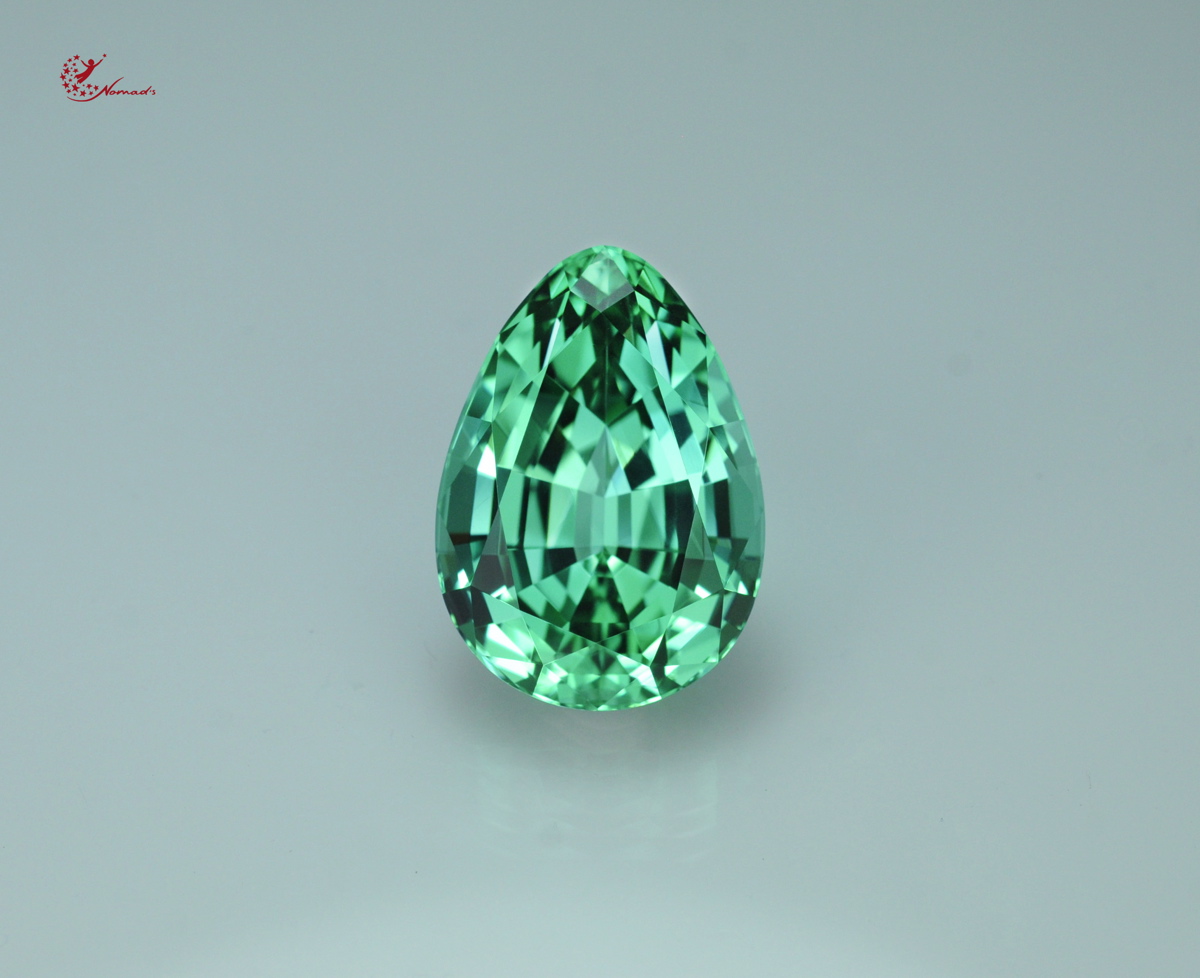

The Namibian stones are highly prized and sought after by connoisseurs, both for their colours and also for their fortunate characteristic of very frequently having an open c-axis. Many of the most extraordinary Namibian tourmalines come from two mines in particular which have acquired almost legendary status: Neu Schwaben and Usakos.

Blue-green tourmaline from the Usakos mine. The cut stone weighs over twenty-eight carats and comes from the pocket discovered in 2016. Photo: Prangrak Ruahong

a- Neu Shwaben

One of Namibia’s oldest and probably best known tourmaline mines, Neu Schwaben is located on the grounds of Neu Schwaben Farm 73, a dozen kilometres south of the town of Karibibib.

Neu Schwaben’s reputation is well deserved: the best indigolite tourmalines that come out of it are absolutely exceptional. In the author’s humble opinion, the Namibian Indigolite tourmalines from Neu Schwaben, Usakos and Katjanga are probably the best in the world along with those from the Mawi mine, Laghman, Afghanistan.

Blue tourmaline “Indigolite” from Erongo. The Namibian stones can easily compete with the finest Afghan or Brazilian Indigolites. Photo: Maria Arkhipova

The history of the Neu Schwaben mine is eventful. For a long time it was owned by Sidney “Sid” Pieters, a local legend (Pietersite, found in Outjo in Namibia, is named after him) who operated several mines in the area (including Usakos, which we will discuss later).

Meanwhile, a major tourmaline discovery in an eluvial deposit in 1996 and 1997 at Neu Schwaben generated a rush and nearly a thousand people from all over the country arrived at the deposit, digging numerous independent shafts.

Although the Namibian Ministry of Mines officially closed the mine, the government allowed some miners to return to Neu Schwaben to mine pegmatite. A few teams of miners, usually of 3 to 5 people each, continue to this day to actively search for tourmaline in some of the shafts of Neu Schwaben, with the eternal hope of finding the pocket of crystals that will make their fortune..

b- Usakos

Almost 90 years ago, near the small town of Usakos, an explosion sounded. A prospector looking for tin had just blown up blocks of rock with dynamite in his concession. Was it a stroke of luck or fate? The dust cleared and to his great surprise, he found tourmalines. And not just a few! He had just opened a gigantic pocket, perhaps the largest ever found in Namibia. It produced a total of 1 tonne of tourmaline crystals! Tin was immediately forgotten and the search for tourmaline began: the Usakos mine was born.

General view of the Usakos mine. Photo: Sébastien Bahri

The mine face at Usakos. The marks of the old dynamite drillings are clearly visible. Photo: Sébastien Bahri

Located a few kilometres from the town of Usakos, this open-pit mine exploits a large pegmatite over 600 metres long and 350 metres wide.

The mine is known for its indigo blue to mint green tourmalines, one of which is a subtle fusion of blue and green, known as a “lagoon” because its colour is close to that of a tropical lagoon. The mine also occasionally produces yellow and red-brown tourmalines. Between 2005 and 2007, several pockets of tourmalines were discovered at Usakos and caused a sensation on the market, both because of their lagoon and electric blue colours and especially because of their size. Magnification-pure gems weighing almost 100 carats were cut.

The neon blue colour of these tourmalines is so visually similar to the copper tourmalines “Paraiba” that they were tested by the Swiss laboratory SSEF. The analyses showed the presence of iron and manganese and the absence of copper.

Just when it was thought that the Usakos tourmalines had been mourned, the mine, seemingly mocking the predictions of humans, gave a superb pocket again in March 2016. Several kilograms of blue-green mint and blue-green lagoon tourmalines were extracted. The Usakos mine will soon be a hundred years old and the pegmatite is still far from being exhausted. Who knows what treasures it still holds?

An exceptional pear-shaped tourmaline of over 64 carats. This is the largest cut gem from the pocket discovered in March 2016. Photo: Prangrak Ruahong

4- Conclusion

As a source of extraordinary tourmalines, Namibia faces major challenges in terms of production. While the Erongo region still holds great potential, several factors are holding back exploration and exploitation of the region’s gem-bearing pegmatites. Much of the land in the region is privately owned and not necessarily interested in seeing mining activity develop on their land. This is compounded by the difficulties of the climate and terrain and the lack of financial resources to launch larger projects.

However, the picture is not entirely bleak. Namibian stones are popular and lagoon and indigo colours are in high demand on the market. The considerable rise in tourmaline prices over the past decade is benefiting local operators by increasing the value of production and making investments in equipment more profitable. It also encourages prospecting in general, which tends empirically to increase the probability of discovering new pegmatites and/or a major pocket.

The rather confidential production in Namibia can also be seen in a positive light. It may seem paradoxical at first, but the small number of players, from the mining itself to the companies working with the material, makes Namibian tourmalines easily traceable from mine to market. With the current strong trend towards traceability and ethics in jewellery, this is an advantage over tourmalines from other origins that may have similar colours.

5- Thanks

I would particularly like to thank Mykola Kukharuk and Sviatoslav Grygorenko for allowing me to make this trip to Namibia, Prangrak Ruahong for his help with the visuals for this article, Christopher L. Johnston for the information provided on the techniques of extraction of Namibian tourmalines and the McDonald family for kindly allowing us to visit the Usakos mine.

6- Bibliography

See you soon!